Executive Summary

Tenant screening is a major driver of housing insecurity. Tenant screening companies collect eviction, credit, and criminal records and repackage them into tenant screening reports that they sell to landlords. This business model has helped entrench eviction records, in particular, as a ubiquitous barrier to housing. Landlords — who often purchase tenant screening reports — regularly reject potential tenants who have any eviction history, regardless of the nature or disposition of their case. People with eviction histories often find themselves locked out of housing opportunities.

To mitigate these harms, many advocates have called for local and state legislation to seal at least some subset of eviction records. However, little guidance exists for people trying to draft such legislation. This issue brief aims to help fill that gap. We offer guidance and recommendations for advocates and policymakers who seek to draft or support eviction record sealing laws.

First, we make the following observations in support of sealing eviction records:

Eviction records should not be used to make housing decisions. Eviction records are products of an unjust, racist, anti-tenant housing system. Using them to screen tenants deepens housing insecurity, discrimination, and conditions of poverty. It also deadens the impact of policies and funding designed to increase access to housing, since many people who qualify for assistance can’t secure housing due to eviction histories. Eviction records also are not reliable proxies for tenant behavior or ability to pay. The vast majority of evictions do not end with a judgment in favor of the landlord, and even those that do are products of a court process that is heavily weighted against tenants.

Sealing eviction records is a critical step toward dismantling harmful tenant screening practices. Sealing eviction records is likely the most effective way to keep them off of tenant screening reports and out of landlords’ rental decisions. Laws restricting landlords’ and tenant screening companies’ use of eviction records are also important, but it’s practically impossible to fully suppress the dissemination and use of eviction records once they become public.

We offer the following guidance for drafting eviction record sealing legislation:

Eviction records should be automatically sealed at the point of filing. As researchers Brian McCabe and Eva Rosen have concluded, “in order for record sealing to be effective, it needs to occur at the moment of filing — not later — since third party companies frequently scrape these records and sell the data to [landlords] for screening purposes.” Moreover, eviction filings are merely unproven allegations and have no legitimate value in rental decisions. Sealing at the point of filing allows tenants to search for new housing while their case is pending and limits landlords’ power to chill tenants from asserting their rights.

Eviction records should remain sealed for as long as possible. Because eviction records are products of housing injustice and discrimination, we don’t believe there are any eviction records that can be fairly used to make housing decisions. If any eviction records are unsealed, it should be as late as possible in the eviction process. For example, unsealing records only after an eviction is executed and the tenant is removed is preferable to unsealing all judgments in favor of landlords, since many tenants continue paying rent even after an eviction judgment, and are never actually removed.

Legislation should provide a process for accessing sealed eviction records for housing justice purposes. Sealing does not need to be a binary system where records are completely open to the public or completely closed. Some access to eviction records may be needed to prevent the immediate harm of eviction and displacement, or to support more transformative change of the housing system. At minimum, the parties to an eviction and their attorneys should have electronic access to their records, and others should be able to request access to records for good cause, including research and reporting. Legal services providers, tenant unions, and similar organizations may need some access to defend against evictions and advance housing justice. The exact scope and methods of access should be determined at the state or local level, based on tenants’ needs and courts’ technical capabilities.

Eviction sealing laws are compatible with the public’s right to access court records. Advocates and policymakers should not be deterred when opponents invoke First Amendment concerns. The public’s access to court records can be, and often is, limited by statute to advance other important interests like access to housing and combatting discrimination.

Advocates and policymakers should engage with courts early in the drafting process to understand courts’ technical capabilities and ensure that they are prepared to implement sealing legislation. Legislative efforts can be derailed if they don’t align with a court’s technical capabilities and resources, or if court officials are resistant to making the necessary systemic changes. All courts have the capacity to seal records in some way, and many courts use software that would allow them to exclude eviction records from public access portals while maintaining electronic access for authorized users. It’s important to understand and account for courts’ technical capabilities; however, existing processes should not be a barrier to sealing eviction records. Legislators should require courts to make the necessary adjustments to their systems, and allocate the funding needed to make those changes.

Eviction is a consequence of a housing system that is unaffordable for too many people, prioritizes the interests of investors and owners, and is built on a history of segregation and discrimination. While we offer strategies on how to limit the downstream effects of eviction records, we reject any premise that evictions should be permissible under a just housing system. But in a world in which evictions persist, sealing eviction records not only lessens the impact of eviction on tenants, but also delegitimizes the tenant screening industry and its claims that these records can or should be used to predict tenancy outcomes. Restricting access to eviction records also helps shift the power relationship between landlords and tenants by limiting landlords’ ability to threaten tenants’ future housing access.

Introduction

Landlords and tenant screening companies rely heavily on eviction records to screen out potential tenants. A large and growing body of research demonstrates how this practice can drive housing insecurity and discrimination. Eviction records are artifacts of housing injustice and systemic racism, and they are created by an eviction court system that heavily advantages landlords. In DC, less than 1% of judgments in eviction hearings are in favor of the tenant.

Tenant screening services and other data brokers have helped entrench eviction records as barriers to housing. These companies collect eviction records as soon as they are filed in court, maintain them in proprietary databases, include them in tenant screening reports that they sell to landlords, and encourage landlords to rely on these records in making rental decisions.

Tenants with eviction histories often find themselves locked out of housing opportunities. In the midst of an affordability crisis, efforts to increase funding for housing assistance are undermined because many renters who qualify for funding get screened out of the housing application process because they have eviction histories.

To address this problem, advocates and policymakers across the country have advocated for legislation to limit the availability and use of eviction records for tenant screening. Several states have passed eviction record sealing laws. Many of these laws only allow people to seal their records after the conclusion of their case, and/or require people to petition the court to seal their records. But support is growing for approaches (such as California’s) that seal eviction records as soon as they are filed, before they become public. Despite this momentum, little guidance exists for advocates and policymakers seeking to draft eviction record sealing legislation.

This issue brief is informed by Upturn’s legislative advocacy efforts in DC — especially our coalition partnerships with direct legal service providers — and our research into the tenant screening industry. In 2019 we began looking into tenant screening companies’ practices by examining their marketing materials, sample tenant screening reports, and other information, including tenant screening contracts, and reports obtained by the Markup and the New York Times. These materials demonstrate that tenant screening still heavily relies on criminal, credit, and eviction records, even if some companies advertise novel technology or data sources.

In 2020, we joined a coalition of DC housing advocates that had formed five years earlier to address barriers to rental housing access in the District. In 2022, largely due to this coalition’s efforts, the DC Council passed major legislation including eviction protections, tenant screening restrictions, and automatic sealing of eviction cases that don’t end in a judgment in favor of the landlord.

While we supported this legislation, we also began pushing (along with a few other advocates) for DC to seal all eviction records immediately at the point of filing. We began talking to coalition partners about how such a law might work, and identified the need for more resources to help advocates and policymakers navigate the questions we were facing.

This issue brief provides recommendations, guidance, and analysis to support anyone considering drafting or advocating for eviction record sealing legislation at the state and local levels. While eviction records policy can be a highly localized issue, we’ve mapped out the common issues and challenges that policymakers and advocates will need to navigate.

Key Concepts

Eviction process

Knowing how the eviction process works in a jurisdiction is necessary to understand how, when, and what kinds of eviction records are created. The eviction process varies by state, but generally follows these stages:

Notice

In most jurisdictions, to begin the eviction process, landlords are required to give the tenant a written notice, which gives the tenant a certain amount of time to comply with the lease terms (e.g., pay outstanding rent) or leave the property before the landlord can file an eviction lawsuit. This notice period can be as little as 24 hours, or up to 60 days.

Filing

After the notice period has elapsed, a landlord may file an eviction lawsuit. In some jurisdictions, the landlord must pay a fee to file. The court then schedules a hearing and formally notifies the tenant of their court date and time.

Court

The court date typically occurs within weeks of the filing. Some landlords and tenants may resolve the issue in the meantime, and those cases are dismissed. Cases may also be dismissed if the judge finds insufficient grounds for the lawsuit or if the landlord does not appear. If the tenant does not appear, then a default judgment for the landlord is entered which allows the landlord to proceed with removing the tenant. If both parties are present for the initial hearing, they may be instructed to attempt to come to an agreement, such as a payment plan. The parties may then file a settlement with the court.

Removal

If the parties cannot come to an agreement, the case will come before a judge for a trial. If the judge rules in favor of the landlord, the landlord receives a judgment for possession and must then obtain a writ of restitution from the court, authorizing the removal of the tenant. The writ is filed with local law enforcement who force the tenant to leave the property. Many states have a right to redemption, which allows a tenant to redeem their tenancy by paying outstanding rent at any time up to, and including, the point at which law enforcement arrives to execute the eviction.

Eviction record

A record is created as soon as a landlord files an eviction lawsuit with the court. The filing typically includes the landlord’s allegation of wrongdoing by the tenant, such as failure to pay rent on time. Right after a landlord files for eviction, the court typically makes the case record publicly available, often accessible through an online portal. As the case proceeds, the publicly available court record may be updated with new information, such as hearing dates and final disposition (such as settlement, dismissal, or judgment).

Sealing

We use the term “sealing” to refer to any restriction on public access to court records or to information contained in those records. Jurisdictions sometimes use other terminology to describe these types of policies, including “masking,” “shielding,” “impounding,” “expungement,” and “confidentiality.” In some cases these terms may be interchangeable, but in some jurisdictions different terms may refer to distinct policies. For example, some courts may view “sealed” records as more restricted from access than “confidential” or “masked” records. We recommend paying attention to these local nuances and adopting the vocabulary that most clearly describes the intended outcomes.

Tenant screening

Tenant screening is any process by which a landlord evaluates and accepts or rejects potential tenants. Tenant screening typically starts with a prospective tenant submitting a rental application and paying an application fee. The landlord uses information submitted in the application — and often other information collected from third parties — to make a rental decision. A landlord might approve the tenant to rent the unit at the advertised price, reject them, or attempt to charge the tenant a higher rent, security deposit, or other fees based on their perceived risk.

Tenant screening company

Many landlords use third-party tenant screening services. These companies use automated systems to match the applicant’s identifying information (such as name, date of birth, and address) to records from various sources, such as credit reporting agencies, proprietary databases, and courts. They parse, categorize, and compile this information into a tenant screening report that they sell to the landlord. Some tenant screening companies present landlords with a menu of screening criteria and thresholds to choose from. Like traditional credit reporting agencies, tenant screening companies are “consumer reporting agencies” subject to fair credit reporting laws.

Tenant screening report

Tenant screening companies compile and repackage records (such as eviction, credit, and criminal histories) into reports that they sell to landlords. Tenant screening companies vary widely in how they package and present the information. Some reports include numerical scores, risk assessments, or recommendations prompting the landlord to accept or reject the tenant. Some reports include only these scores or recommendations with no details about the factors used to generate them.

Eviction records should not be used to make housing decisions.

The tenant screening industry profits from repackaging eviction records and encouraging landlords to universally use them as screening criteria. Landlords often reject tenants on the basis of any eviction record. But tenant screening companies mislead landlords about what eviction records represent. Eviction histories are not reliable indicators of tenants’ behavior or ability to pay rent, and they are products of an unjust, racist, anti-tenant housing system. Using them to screen tenants deepens housing insecurity, discrimination, and conditions of poverty.

A. Tenant screening companies profit from repackaging eviction records, which drives housing insecurity.

Tenant screening companies have played a central role in entrenching eviction records as overwhelming barriers to housing. While some tenant screening companies boast about their use of cutting-edge technology or novel data sources, they largely repackage criminal, credit, and eviction records.

Data brokers — including tenant screening companies and third parties that sell records to tenant screening companies — often collect eviction records from online court databases as soon as they become available, usually right after a landlord files for eviction. Even if court records are later sealed, some companies may continue to retain and disseminate them. Once an eviction record becomes publicly available, it is practically impossible to effectively suppress it.

Some tenant screening reports are designed to encourage landlords to accept or reject tenants based solely on the report’s contents, score, and/or recommendation.For example, National Tenant Network (NTN)’s DecisionPoint product scores applicants from 0 to 100, indicating whether they meet or fall short of specific criteria. Some tenant screening reports provide these types of recommendations without sharing the underlying records or details with the landlord.

Figure 1. National Tenant Network’s sample DecisionPoint tenant screening report

![This figure shows National Tenant Network’s sample DecisionPoint tenant screening report. It shows a score range where a score of 59–00 “does not meet” the rental criteria, 79–60 “conditionally meets” the criteria, and 100–80 “meets” the criteria. The sample report shows an applicant score of 55 and explains that the applicant “does not meet criteria” because of an eviction “[j]udgment for [p]laintiff” for $1,000.](http://images.ctfassets.net/bicr1ie5o2cw/3XDa0Hb3hgt5r7PJVvvRyM/2e29eee68631419cf49cd06550eefa74/Figure_1.jpg)

This figure shows National Tenant Network’s sample DecisionPoint tenant screening report. It shows a score range where a score of 59–00 “does not meet” the rental criteria, 79–60 “conditionally meets” the criteria, and 100–80 “meets” the criteria. The sample report shows an applicant score of 55 and explains that the applicant “does not meet criteria” because of an eviction “[j]udgment for [p]laintiff” for $1,000.

Tenant screening companies sometimes use marketing language or design elements encouraging landlords to rely on their findings or conclusions. NTN advertises its analysis as “comprehensive” and states that it tells landlords “everything [they] need to make a sound rental decision.” However, companies’ terms of service often disclaim any legal liability for making housing decisions or for providing reports or scores that don’t accurately predict relevant outcomes. For example, RealPage’s terms require landlords to agree not to hold RealPage liable for “any failures of [its] [s]cores to accurately predict that a [] consumer will repay their existing or future credit obligations . . . .”

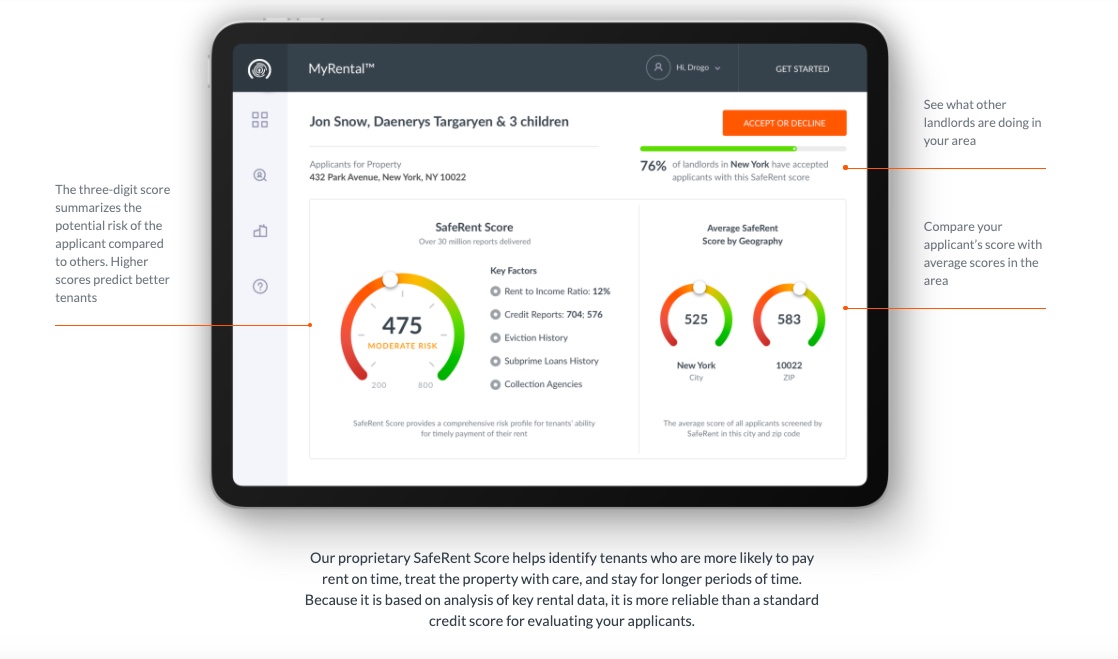

Figure 2. SafeRent’s sample tenant screening report

Figure 2 shows an image of a sample tenant screening report from SafeRent’s website. This image shows a score range of 200 to 800, where the hypothetical tenants received a score of 475, or “moderate risk.” Next to the score is a list of “key factors,” which includes rent to income ratio, credit reports, eviction history, subprime loans history, and collection agencies. Text underneath the image of the sample report says “Our proprietary SafeRent score helps identify tenants who are more likely to pay rent on time, treat the property with care, and stay for longer periods of time. Because it is based on analysis of key rental data, it is more reliable than a standard credit score for evaluating your applicants.”

Tenant screening reports entrench the false idea that any eviction record is a major red flag for a potential tenant. For example, NTN’s sample tenant screening report indicates that the hypothetical tenant received a failing score primarily on the basis of an eviction record, even though the fine print on the following page warns that eviction records may be inaccurate or may not represent a lease violation. However, as we explain in the following sections, these records do not represent tenants’ ability to pay rent or uphold their lease; they represent structural discrimination in the systems that created them, and conditions of poverty — all of which are exacerbated by making housing inaccessible to people with records.

B. Tenant screening companies report inaccurate and misleading eviction records.

Tenant screening reports and the records they include are frequently error-ridden. This rampant inaccuracy is due to the methods companies use to compile reports, inaccuracies or lack of information in court records databases, market forces that tolerate and reward inaccurate and overinclusive reports, and inadequate enforcement of laws requiring tenant screening companies to ensure accuracy. A 2020 study found that, on average, 22% of eviction records contained ambiguous information on how the case was resolved or falsely represented a tenant’s eviction history. A lawsuit against tenant screening company RealPage alleged that the company produced 11,000 inaccurate reports between 2014 and 2019 using “abbreviated” criminal records, which are cheaper than full reports and do not include details of the resolution or complete dates of birth, making it harder to accurately match a person with a record. In 2020, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) settled with AppFolio over allegations that AppFolio did not check the accuracy of criminal records it included on tenant screening reports, and that it sold reports with mismatched records and inaccurate case dispositions, causing people to be denied housing. Legal Aid attorneys have found DC residents’ sealed records in Bloomberg Law’s research database, accessible to all subscribers. These practices continue despite decades of federal enforcement efforts and litigation.

Tenant screening reports mislead landlords about what eviction records represent and their predictive value. The vast majority of evictions are filed for alleged nonpayment of rent, yet tenant screening companies sometimes claim that eviction records indicate other types of risk, such as the risk that a tenant will damage the property. For example, AAA Credit Screening Services encourages landlords to check eviction records to reduce landlords’ risk of legal responsibility for tenants’ criminal activities. TransUnion, one of the largest consumer credit reporting agencies, advises landlords that checking eviction histories protects against “lost rent, property repairs, and eviction-related expenses.”

C. Eviction records primarily reflect landlords’ behavior and incentives, not tenants’ behavior.

1. Eviction records often do not indicate any wrongdoing by a tenant.

Eviction records are not reliable evidence that a tenant broke their lease, or that their landlord had a legal reason to evict them. Many eviction filings do not even allege that the tenant did anything wrong. Most jurisdictions allow landlords to file for eviction for reasons that involve no fault (or without “good cause”), such as the landlord deciding to remove their property from the rental market. In King County, WA, no-cause terminations were the second most common basis for evictions in 2019.

Even when fault is alleged, the fact that a landlord filed an eviction does not mean any wrongdoing by the tenant was found. There is a large gap between the number of evictions filed against tenants and the number of judgments landlords actually win in court. A study of eviction records in DC by Brian McCabe and Eva Rosen found that 69% of evictions filed for nonpayment of rent in 2018 were dismissed — meaning there were insufficient grounds for filing the eviction, the tenant paid the rent owed before their hearing, or the landlord failed to attend the hearing. An even smaller percentage of those filings result in executed evictions, where a tenant is legally required to move out of their home. In DC, McCabe and Rosen found that landlords executed only 5.5% of evictions filed in 2018. Some eviction judgments go unexecuted because the tenant pays the rent they owe, and/or the landlord continues to accept their monthly rent payments. In Baltimore, less than half of all filed evictions result in judgments for the landlord, and only 4.3% of all evictions are ultimately executed. In 2017, only 9% of eviction filings in New York City were executed.

The gap between filed and executed evictions is so large because landlords have more incentive to file evictions than to execute them. For landlords, the cost of an eviction filing is low. In the largest American cities, the median filing fee for landlords to file an eviction lawsuit is $106. In DC, the filing fee is just $15. Some landlords routinely file evictions against their tenants, even filing multiple evictions against the same tenant (known as “serial filing”), rather than working with them to resolve rent or maintenance issues. In Baltimore, landlords file for eviction approximately 150,000 times per year, while the city only contains 130,000 renter households. In DC, 20 landlords were responsible for almost half of all evictions filed in 2018. The threat of eviction allows landlords to leverage the state’s police power to collect on missing rent, even if they are unlikely to execute the eviction because of the costs related to vacancy and property turnover. Often, an eviction filing for nonpayment of rent is a landlord’s first resort to collect money.

2. Eviction records do not reflect applicants’ ability to pay rent.

Tenant screening companies often present eviction records as a proxy for a renter’s ability to pay. But eviction records often do not reflect tenants’ present financial situations, for several reasons. First, tenants who have cause to withhold rent due to poor living conditions sometimes have evictions filed against them for missed rent. Additionally, many tenants with eviction filings are able to make consistent late payments that the landlord still accepts, sometimes because they get paid or receive financial aid after rent is due. Finally, missed rent payments can be due to financial circumstances that are likely to change, such as job loss. Many people who are named in eviction filings for missed rent payments have since received housing vouchers or other rental assistance that directly demonstrates their ability to pay.

Landlords almost always ask for prospective tenants’ current income information on rental applications, which should obviate the need to use unreliable eviction records as a basis for predicting whether someone can pay rent. Yet, tenants, especially those with housing vouchers, are often screened out of housing they can afford because of their eviction histories. A recently filed lawsuit against tenant screening company SafeRent alleges that the company violated the Fair Housing Act and state source-of-income discrimination laws by giving disproportionately low scores to renters of color who use housing vouchers to pay their rent, leading to them being denied housing. In response to discrimination against voucher holders, DC Council recently passed a law banning landlords from screening out tenants with housing vouchers based on negative rental or credit history they incurred before receiving their vouchers.

D. Eviction records are products of an unjust, racist system.

Tenant screening has more than just an accuracy problem. Even when records accurately indicate a judgment against the tenant, they reflect systematic power imbalances in the housing system that disproportionately impact low-income people of color.

1. Landlords are significantly advantaged in the eviction court process.

Even when a landlord wins an eviction judgment, those records represent a vast power and resource imbalance between landlords and tenants in eviction proceedings. Many tenants lose their eviction cases simply because they are unable to appear at their hearing. In Philadelphia, default judgments are issued in about 33% of all landlord-tenant cases. This is often because the tenant did not receive their eviction notice, cannot afford to take time off work, or cannot find transportation to the court. In 2019, lack of notice accounted for 21% of all default judgments in Philadelphia’s eviction courts. In a survey of tenants with eviction filings in Baltimore, participants expressed that the value of appearing in court was outweighed by the cost of lost time and wages.

Even those who are able to appear at their hearings typically do not have the resources to defend themselves or navigate the eviction process. Most jurisdictions do not require free legal representation for tenants. On average, in jurisdictions without a right to counsel, only 3% of tenants facing eviction in 2022 had lawyers, compared to 81% of landlords. Studies of eviction proceedings describe a “one-sided, factory-like process in favor of landlords.” For example, in 2002, the average time for hearing a case in Chicago’s housing court was 1 minute and 44 seconds. Unsurprisingly, this inequitable process produces lopsided results: In DC, less than 1% of judgments are in favor of the tenant.

2. Eviction disproportionately burdens Black and brown tenants, particularly Black women.

On average, Black renters have evictions filed against them at twice the rate of white renters. However, Black women are also more likely to have a prior eviction filing that ultimately resulted in a dismissal. In Massachusetts, Black women renters were found to be three times more likely to see their eviction cases dismissed. In other words, Black women are more likely to be subject to illegitimate eviction filings, and most likely to be further denied future housing due to those records. Eviction filings are more likely to be a proxy for race — as well as for source-of-income and familial status — than for any real indicator of tenant behavior or ability to pay.

Recently, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) issued new fair housing guidance to subsidized multifamily properties, noting that screening criteria, including eviction histories, “may operate unjustifiably to exclude individuals based on their race, color, or national origin,” and that negative records should not trigger an automatic denial of tenancy. Given the racist distribution of eviction filings, their use in tenant screening is unjustifiable and can only deepen racial injustice in access to housing.

Sealing eviction records is a critical step toward dismantling harmful tenant screening practices.

In a growing number of cities and states, tenant advocates and policymakers are trying to limit eviction records as a barrier to housing. To date, legislative reform efforts primarily include: (1) “fair chance housing laws,” which limit the criteria and records landlords can use to screen tenants, and usually strengthen tenants’ access to information about and ability to challenge the screening process; (2) consumer reporting laws, which can limit what companies include in tenant screening reports; and (3) eviction sealing measures, which limit public access to certain court records.

These approaches can suppress access to or use of eviction records at different points in the tenant screening process: Fair chance housing laws try to stop or limit landlords’ reliance on eviction records, but can’t guarantee that landlords won’t see the records. Consumer reporting laws may prevent certain records from appearing in tenant screening reports (where landlords are likely to see them), but don’t suppress the records in other sources, like court databases. And sealing — especially at the point of filing — keeps records from being accessible to the public in the first place.

These approaches can be complementary, but sealing eviction records at the point of filing is the only one designed to suppress eviction records at their source, ensuring that they can’t be accessed for use in housing decisions. Sealing eviction records acknowledges that they are products of injustice and shouldn’t be used to make decisions about people. Eviction record sealing can also bolster the protections of existing laws: for example, multiple federal agencies have warned that reporting sealed records can be evidence of Fair Credit Reporting Act violations.

Depending on the dynamics in a particular jurisdiction, it may be strategic to simultaneously advocate for multiple legislative approaches, or to combine them in the same legislation. For example, housing advocates in DC successfully combined tenant screening, eviction record sealing, and other eviction protections in the same legislation. In some places, such as Philadelphia, advocates have prioritized tenant screening protections because the local or state governments or legal regimes are more hostile to sealing.

Of course, sealing laws come with their own challenges and complexities, which we address in the following guidance.

Guidance for drafting eviction record sealing legislation

This section provides recommendations and guidance for people drafting eviction record sealing laws. Eviction is a consequence of a housing system that is unaffordable for the majority of people, prioritizes the interests of investors and owners, and is built on a history of segregation and discrimination. While we offer strategies on how to limit the downstream effects of eviction records, we reject any premise that evictions should be permissible under a just housing system. But in a world in which evictions persist, sealing eviction records not only lessens the impact of eviction on tenants, but also delegitimizes the tenant screening industry and its claims that these records can or should be used to predict tenancy outcomes. Restricting access to eviction records also helps shift the power relationship between landlords and tenants by limiting landlords’ ability to threaten tenants’ future housing access.

A. Automatically seal eviction records.

Eviction sealing can be petition-based or automatic. When records are sealed automatically, all records that meet certain criteria are sealed. For example, in DC, eviction records that do not result in a judgment in favor of the landlord are automatically sealed within 30 days of the conclusion of the case. All other eviction records are sealed after three years. Petition-based sealing typically requires a tenant to submit a request to the court, requiring a judge to decide whether the record can be sealed. Petition-based sealing laws often involve court discretion, requiring the court to weigh factors such as the legitimacy of the original eviction filing and the public’s interest in keeping the record accessible. The sealing petition often must overcome an explicit policy favoring public access to court records. Recent petition-based sealing laws in Virginia and DC attempt to remove judges’ discretion, requiring the court to seal records where certain showings are made.

Petition-based sealing burdens tenants with paperwork and protects few tenants from the impact of eviction records. Under petition-based sealing laws, sealing is not guaranteed and there are significant barriers to even making a request. First, in jurisdictions without a right to counsel, most tenants are self-represented and typically lack the legal knowledge to pursue sealing. Second, petition-based sealing is only intended to be available to a small minority of defendants. The majority of landlord-tenant disputes, which concern failure to pay rent, would not be eligible for sealing under most petition-based sealing criteria. Third, leaving eligibility for sealing up to the court allows for the same kind of biases that exist in other parts of the judicial system. By design, petition-based sealing protects few tenants from the adverse effects of having an eviction record.

Petition-based sealing can and should be permitted even when most records are automatically sealed. For example, in DC, tenants can ask the court to seal an eviction judgment before the three-year automatic sealing period in a number of circumstances, including if the judgment for the landlord was for $600 or less, if the tenant was evicted from a subsidized housing unit, and if the tenant shows that they faced a retaliatory eviction.

B. Seal eviction records at the point of filing.

Records can be automatically sealed either post-filing or at the point of filing. In post-filing sealing legislation, eviction records are sealed if certain conditions are met — usually at the conclusion of the case — such as a judgment against the landlord, a foreclosure, or a dismissal. Records are typically still made public when the landlord files for eviction, and are later sealed within some number of days of the final disposition or another qualifying event.

Point-of-filing sealing laws, on the other hand, require courts to seal records when a landlord files for eviction, so the records never become public unless they are later “unsealed.” These laws also usually allow for petition-based sealing, where tenants that do not meet the specified criteria can still request sealing on another basis. Point-of-filing sealing laws may also list the parties that are permitted access to the sealed records, which usually includes parties to the case, their attorneys, and third parties with “good cause” to request access to records, such as for journalism and research.

Sealing eviction records at the point of filing is the most effective sealing policy for suppressing eviction records, especially because data brokers regularly scrape records directly from court websites, incorporating them into proprietary databases as soon as the court makes the information public. Even if the record is later sealed, it might remain in a company’s database and be reflected in tenant screening reports. Attempting to suppress records once they’ve been made public is incredibly difficult if not impossible. By limiting data broker access, sealing at the point of filing makes it far less likely that eviction records will be included in tenant screening reports.

Recently, several organizations have called for sealing at the point of filing, citing its advantages for keeping eviction filings out of the tenant screening process. The DC Council Office of Racial Equity concluded that sealing eviction records post-filing would merely maintain the status quo of racial inequity, and that records would need to be sealed immediately upon filing to improve racial equity in rental housing decisions. And the American Bar Association adopted ten guidelines for eviction laws, including that courts “should automatically seal the names of defendants before a final judgment and in dismissed cases[,]” noting that the efficacy of sealing is limited when records are not sealed until after they are made public.

C. Keep eviction records sealed for as long as possible.

In general, anyone can petition a court to reopen a sealed record. But in states where point-of-filing sealing laws have been passed or considered, they have typically provided for a subset of sealed eviction records to be automatically “unsealed” when certain criteria are met (for example, after a judgment has been entered).

Records should be unsealed as late in the eviction process as possible, if at all, in order to protect the most tenants. How late records can be unsealed may depend on a jurisdiction’s eviction process and the court’s ability to unseal records. Drafters may need to identify a point in the eviction court process, between judgment and removal, that the court can use to “trigger” unsealing. In some jurisdictions, this may mean records are made public once there is a judgment for the landlord. In California, records are unsealed if the landlord wins a judgment within 60 days. A proposed sealing bill in Connecticut would have unsealed evictions only if a judgment was entered for the landlord at trial.

The justification for unsealing evictions after a judgment for the landlord is that the landlord has shown cause for the eviction to an independent court, presumably making these records a better indicator of a tenant’s suitability. However, as previously discussed, the eviction court process is heavily weighted in favor of landlords due to lack of representation for tenants, notice problems, insufficient time spent adjudicating cases, and barriers to tenants being able to make their court dates. Many eviction cases result in a judgment in favor of the landlord despite no wrongdoing by the tenant.

Additionally, many tenants, especially poor tenants, would likely not qualify for permanent sealing. The vast majority of evictions are for failure to pay rent. Landlords are typically legally permitted to evict on this basis, and judgments in these cases are more likely to go to landlords than to tenants. As a result, many of these records would become unsealed, pushing low-income tenants into greater economic and social precarity. Even when an eviction judgment accurately represents a tenant’s failure to pay rent, it’s only a “brief snapshot of a person going through a difficult period,” and does not account for the tenant’s current financial situation, which landlords can (and often do) evaluate based on income, including vouchers.

Ideally, records should remain sealed even after a judgment is entered against the tenant. Unsealing at the latest point in the eviction process, such as after the writ is executed and the tenant is forced to leave the property, protects tenants who are able to redeem their tenancy by paying outstanding rent or resolving the lease violation. Unfortunately, unsealing evictions even this late in the process protects all but the most vulnerable tenants, and potentially scapegoats them as “deserving” of eviction and its downstream consequences.

Ultimately, unsealing of any kind leaves too many tenants behind. The eviction court process today is fatally unjust to tenants. Under these conditions, we don’t believe there are any eviction records that can fairly be used to make housing decisions without perpetuating this unjust and discriminatory system. However, we recognize that drafters may need to make a decision about when to unseal records, and in that case we encourage unsealing as late in the eviction process as possible and addressing the underlying problems with the judicial process.

D. Maintain limited electronic access to sealed eviction records for housing justice purposes.

A sealing regime does not need to be a binary system in which records are completely open to the public or completely closed. While sealing is intended to reduce harm from evictions to people searching for housing, some access to eviction records may be needed to prevent the immediate harm of eviction and displacement, or to support more transformative change of the housing system. The benefits of allowing some access to sealed records to advance housing justice should be carefully weighed against the risk that access could be misused to sell eviction records. To help mitigate this risk, legislation should limit the permissible purposes for accessing records, not just the parties that can obtain access. The exact scope and methods of access will need to be determined at the state or local level, based on tenants’ needs and courts’ technical capabilities. Some parties that may need access to sealed eviction records include:

Parties to an eviction case, their attorneys, and other occupants of the unit: Tenants named in an eviction filing and their attorneys need access to the court records so that they can defend themselves against the eviction and have a record of the disposition of their case. Courts routinely allow parties and their attorneys to access sealed or confidential records. Additionally, as Nathan Leys, formerly of the New Haven Legal Assistance Association, pointed out, landlords might mistakenly fail to name some occupants of the unit when they file an eviction action, and those occupants also need access to the case records.

Legal and other direct service providers: Legal services organizations use eviction records to reach out to people who have evictions filed against them, advise them on the eviction process, and offer pro bono representation. Because of failures by landlords and process servers to notify tenants of evictions, some tenants only find out that an eviction case has been filed against them because of this outreach. Some advocates also use information from eviction records to do outreach and offer help applying for rental assistance or eviction diversion programs.

DC’s eviction sealing law allows any attorney authorized to practice in DC who is “considering commencing representation of the tenant” to request access to sealed eviction records. California does not provide general access to legal organizations but requires courts to mail a notice to each person named in an eviction action. The notice informs people of the steps they need to take to avoid eviction and directs them to legal service providers and rental assistance. To prevent misuse, legislation should prohibit or limit further disclosure of records accessed by attorneys and other service providers.Tenant unions and organizers: Tenants and organizers also use eviction records to learn about and prevent the immediate harms of eviction filings. Access to records can help tenants build power and fight for more transformative change, for example, by organizing with neighbors to collectively fight evictions, or by tracking where evictions occur and which landlords are the biggest evictors. The needs of tenants in a given jurisdiction should inform the scope and methods of access to sealed records. Ultimately, transformative change in the housing system is necessary so people don’t need to rely on access to court records to remain in their homes.

Researchers, journalists, and others with “good cause” requests: Research and reporting on eviction records have created critical knowledge about the nature and distribution of evictions. For example, Josh Kaplan’s reporting for DCist used eviction court records to show that eviction process servers were routinely failing to effectively serve tenants in DC with notice that they had been named in eviction filings. This, along with other research including a report on evictions in DC by Brian McCabe and Eva Rosen, helped convince legislators to address these issues.

Researchers commonly submit bulk records requests to courts, and not all research projects require the parties to a case to be identified. Both California’s and DC’s eviction sealing laws allow the court to grant access to sealed records for research and reporting, with limitations on access to identifiable records. These requests typically fall under “good cause” access provisions. In some cases, researchers may need identifiable eviction records to extract or infer demographic data to study the discriminatory impacts of eviction. DC’s eviction record sealing law establishes a procedure to request identifiable eviction records. For example, requesters must provide “documented procedures to protect the confidentiality and security of the information.”

Where access to sealed records is needed, electronic access should be available. Courts often require tenants and their attorneys to access sealed records in person, which can be an onerous barrier to getting representation and defending against an eviction. In DC, advocates negotiated with the Superior Court and City Council to require the court to make sealed records available “by an electronic means designated by [the court].”

Courts and legislatures should make more aggregate data on evictions available to the public. The Right to Counsel NYC Coalition’s demands include making eviction case filing data public “in a way that protects tenants’ identity and information, so that tenants can have better data about landlords’ actions.” New America’s Future of Land and Housing program has proposed that California make aggregate (or de-identified) eviction data available to the public.

E. Eviction sealing laws are compatible with the public’s right to access court records.

Some opponents — particularly industry groups — have tried to defeat eviction record sealing proposals by invoking First Amendment concerns. However, this should not deter advocates or policymakers from advancing legislation. Sealing laws are common and justifiable limitations on public access to court records. This section is intended to help advocates and policymakers anticipate and respond to these concerns.

1. The right to access court records is not absolute.

The public has a limited right to access court proceedings, including some court records, to protect “the proper functioning of the judicial process and the government as a whole,” and “the free discussion of governmental affairs.” The Supreme Court has never acknowledged a right to access civil court records, but several lower and state courts have, and in some jurisdictions this right could extend to eviction records.

However, the right to access court records is not absolute. State and local governments can — and regularly do — pass laws that limit access to court records to protect important interests like access to housing.

Unlimited and unregulated public access to eviction records (along with other anti-tenant court processes) has undermined tenants’ access to fair hearings. The prospect of having an eviction record chills tenants from fighting their evictions in court. As the American Bar Association acknowledged, this “dynamic [] undermines the fundamental legitimacy of the judicial forum.” Sealing eviction records is not only allowable but necessary to preserve tenants’ access to the courts.

Courts vary in their approaches to analyzing right-to-access cases, but they generally consider whether sealing advances a significant or compelling state interest, and whether the sealing measure is appropriately tailored to advance that interest, including whether alternative measures that don’t burden access to court records could accomplish the same goal.

2. Protecting access to housing and combatting discrimination are valid reasons to limit the public’s access to court records.

Governments can limit access to court records to protect housing access and combat discrimination. In U.D. Registry v. State of California, the California Court of Appeals found that “concern about the availability of rental housing for those needing housing, and particularly those facing eviction, is a valid and significant state interest.” In Yim v. City of Seattle, the US District Court for the Western District of Washington found that Seattle had a substantial interest in reducing racially discriminatory barriers to housing.

Public access to court records can also be limited “ . . . where court files might have become a vehicle for improper purposes.” Clearly, eviction records have become a vehicle for improper purposes. Eviction records have become a profitable commodity for data brokers at the expense of fair housing. Even when these practices violate fair housing and fair credit reporting laws, tenants struggle to hold anyone accountable. They are seldom able to correct inaccurate records at all, let alone in time to secure an apartment. This market for eviction records also chills tenants from asserting their rights and makes it easier for landlords to evict tenants with no real process.

3. Sealing laws can be tailored to preserve access to the courts.

Sealing laws are not a binary on/off switch for all access to eviction records. They can and should allow tenants and other parties to access records as needed to effectively defend against and prevent evictions, and advance housing justice. Sealing laws typically allow people to request access to sealed records for good cause, such as journalism and research. Eviction sealing laws can also be an opportunity to enhance access to courts and eviction data by requiring courts to provide notice to tenants, including resources for legal help, and requiring public disclosure of aggregate eviction statistics. Where feasible, some jurisdictions might consider maintaining a public database but removing tenants’ names and other personal information.

4. Alternatives to sealing eviction records at the point of filing offer incomplete protection.

Of the eviction records policies that have been proposed, sealing at the point of filing is most likely to keep eviction filings out of private databases and off of tenant screening reports. By limiting access to records in the first instance, jurisdictions can make more affirmative choices about the appropriate circumstances under which records can be made publicly available. Delaying sealing to a later point (e.g., until after the conclusion of a case) is limited in its effectiveness because it still allows data brokers and others to collect and disseminate eviction filings before they’re sealed. Similarly, while laws regulating landlords’ and tenant screening companies’ use of eviction records are important complements to sealing, they are not alternatives to sealing eviction records at the point of filing.

F. Work with courts to ensure sealing will be implemented.

When legislatures pass eviction sealing laws, courts must adapt their records systems to comply. Legislative efforts can be quickly derailed if they don’t align with the court’s technical capacity and resources, or if court officials are resistant to making the necessary systemic changes. Advocates and policymakers should engage court personnel early on in the drafting process to make sure that courts will be able to implement the legislation.

Luckily, courts almost always have some capacity to maintain confidential case information that can be accessed by certain people — such as court personnel and parties to the case — but not by the general public. While some jurisdictions build their own case records management systems, many contract with vendors to provide these services. One of the largest of these vendors is Tyler Technologies, which claims its Odyssey court records management products are implemented in at least 28 states.

Advocates and policymakers should be cognizant of three key court technology systems that can impact the ability to seal records: (1)E-filing systems, which allow people to file documents with the court; (2) case records management systems, which allow courts to track, update, schedule, and process case information; and (3) online access portals, which allow the general public or certain credentialed parties to access court records.

1. E-filing systems can limit the information included in documents filed with the court.

E-filing systems, and the rules e-filers must follow, dictate what information must be included in the court filing, what information must be excluded, and what information must be filed under seal. Many courts use e-filing rules to protect certain personal information from disclosure. For example, many courts prevent the names of minors, social security numbers, and other sensitive information from being included in court filings or appearing in public court records. E-filing systems review filings for compliance with these rules, usually along with some manual review by clerks, before making them available for others (such as other court personnel or members of the public) to see.

E-filing systems and rules could be used to prevent tenants’ identifying information from ever entering court filings, or from being included in publicly available court documents. For example, as is common in juvenile cases, courts could require landlords filing evictions to only include the defendant’s initials or a pseudonym, rather than their full name.

2. Case records management systems can allow courts to assign different levels of confidentiality to different types of records.

Case records management systems often include the ability to designate certain documents as sealed or confidential and control who has access to those records. California’s contract with Tyler Technologies includes the ability to assign different levels of confidentiality and access restrictions to different types of cases, and the ability to seal cases immediately upon filing and unseal them when certain conditions are met.

Even in states with the strongest public access laws, there are always many types of confidential records in the court’s system. These records can include discovery material, adoption records, and the many case records that get sealed pursuant to statutes or petitions.

3. Courts use portals to provide limited access to the general public and privileged access to certain parties.

Courts usually maintain public access portals that people can use to see docket information and case records that have not been categorized as sealed or confidential. Some of these systems allow certain people or organizations to register for enhanced access to records through the same or a different portal. For example, Vermont’s Odyssey portal allows parties to a case, attorneys of record, as well as other agencies and organizations that have agreements with the judiciary, to log in to the portal to access records not available to the general public.

Courts with these types of systems can use different levels of portal access to keep identifiable eviction records out of public portals while maintaining access for the parties to the case and their attorneys. They could also provide access through the portal — using memoranda of understanding (MOUs) or other agreements — to legal services organizations, tenant unions, or other designated parties for the limited purpose of helping prevent and defend against evictions.

Conclusion

The need for eviction records sealing is urgent. The economic impact of the pandemic has left millions of renters thousands of dollars behind in rent. The rising number of eviction filings will likely exacerbate the homelessness crisis, in part because of the collateral effects of eviction records. Landlords and tenant screening companies have shown that they won’t voluntarily stop screening people based on eviction records despite the evidence of discriminatory impact. Luckily, momentum is building across the country for eviction record sealing, with legislatures passing new sealing laws and institutions calling for sealing records at the point of filing. This issue brief has set forth some recommendations for how eviction sealing laws can be most effective and how to navigate common challenges drafters may face. Eviction records policy can be highly localized and we encourage advocates and policymakers to conduct research and experiment with sealing policies at the state and local level.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for reviewing an earlier draft of this issue brief: Rasheedah Phillips, Director of Housing, PolicyLink; Sabiha Zainulbhai, Senior Policy Analyst, Future of Land and Housing, New America; Wonyoung So, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Mel Zahnd, Senior Staff Attorney, Legal Aid DC.

1

See, e.g., Esme Caramello & Nora Mahlberg, Shriver Center, Combating Tenant Blacklisting Based on Housing Court Records: A Survey of Approaches 1, Sep. 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20181025193012/http://povertylaw.org/files/docs/article/ClearinghouseCommunity_Caramello.pdf (quoting Teri Karush Rogers, Only the Strongest Survive, N.Y. Times, Nov. 26, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/26/realestate/26cov.html) (“It is the policy of 99 percent of [On-Site’s] customers in New York to flat out reject anybody with a landlord-tenant record, no matter what the reason is and no matter what the outcome is, because if their dispute has escalated to going to court, an owner will view them as a pain.”); Community Legal Services of Philadelphia, Breaking the Record: Dismantling the Barriers Eviction Records Place on Housing Opportunities 9, Nov. 2020, https://clsphila.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Breaking-the-Record-Report_Nov2020.pdf [hereinafter “Breaking the Record”]; Eric Dunn & Marina Grabchuk, Background Checks and Social Effects: Contemporary Residential Tenant-Screening Problems in Washington State, 9 Seattle Journal for Social Justice 319, 336, 2010; Rudy Kleysteuber, Tenant Screening Thirty Years Later: A Statutory Proposal to Protect Public Records, 116 Yale L. J. 1344, 1347, 2007; Nathan Leys, Testimony in support of H.B. 6528, before the Connecticut General Assembly Housing Committee 1, 2021, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2021/hsgdata/tmy/2021HB-06528-R000304-Leys,%20Nathan-Sealing%20Eviction%20Records-TMY.PDF; Complaint 1, 4, Smith v. Wasatch Property Management, Inc., 2:17-cv-00501 (W.D. Wash., Mar. 30, 2017).

1

See generally, e.g., Breaking the Record, supra note 1; Peter Hepburn, Renee Louis & Matthew Desmond, Eviction Lab, Racial and Gender Disparities among Eviction Americans, Dec. 16, 2020, https://evictionlab.org/demographics-of-eviction/; Mathew Desmond, Eviction and the Reproduction of Urban Poverty, 118 Am. J. Sociology 88, 2012; Brian J. McCabe & Eva Rosen, Eviction in Washington, DC: Racial and Geographic Disparities in Housing Instability, Fall 2020, https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/8cq4p8ap4nq5xm75b5mct0nz5002z3ap; Sophie Beiers, Sandra Park & Linda Morris, Amer. Civ. Liberties Union, Clearing the Record: How Eviction Sealing Laws Can Advance Housing Access for Women of Color, Jan. 10, 2020, https://www.aclu.org/news/racial-justice/clearing-the-record-how-eviction-sealing-laws-can-advance-housing-access-for-women-of-color; Matthew Desmond, MacArthur Foundation, Poor Black Women are Evicted at Alarming Rates, Setting off a Chain of Hardship, Mar. 2014, [https://www.macfound.org/media/files/hhm_-poor_black_women_are_evicted_at_alarming_rates.pdf](https://www.macfound.org/media/files/hhm-_poor_black_women_are_evicted_at_alarming_rates.pdf); Sandra Park, Am. Civ. Liberties Union, Unfair Eviction Screening Policies are Disproportionately Blacklisting Black Women, Mar. 30, 2017, https://www.aclu.org/blog/womens-rights/violence-against-women/unfair-eviction-screening-policies-are-disproportionately; Caramello & Mahlberg, supra note 1; Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr., Salt in the Wound: How Eviction Records and Back Rent Haunt Tenant Screening Reports and Credit Scores, Aug. 2020, https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/special_projects/covid-19/IB_Salt_in_the_Wound.pdf; Lydia X. Z. Brown, Ctr. for Democracy & Tech., Tenant Screening Algorithms Enable Racial and Disability Discrimination at Scale, and Contribute to Broader Patterns of Injustice, July 7, 2021, https://cdt.org/insights/tenant-screening-algorithms-enable-racial-and-disability-discrimination-at-scale-and-contribute-to-broader-patterns-of-injustice/.

1

See, e.g., Allyson E. Gold, How Eviction Courts Stack the Deck Against Tenants, The Appeal, Apr. 13, 2021, https://theappeal.org/the-lab/explainers/how-eviction-courts-stack-the-deck-against-tenants/; Am. Bar Assoc., Ten Guidelines for Residential Eviction Laws, Guidelines 3–6, 8–9, March 14, 2022, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_aid_indigent_defense/sclaid-task-force-on-eviction–housing-stability–and-equity/guidelines-eviction/; Kathryn A. Sabbeth, Erasing the “Scarlet E” of Eviction Records, The Appeal, Apr. 12, 2021, https://theappeal.org/the-lab/report/erasing-the-scarlet-e-of-eviction-records/ (“[E]normous numbers of defendants lose by default and the vast majority have no lawyer.”); Russell Engler, Connecting Self-Representation to Civil Gideon: What Existing Data Reveal About When Counsel is Most Needed, 37 Fordham Urban L.J. 37, 46–51 (2010); Kathryn Ramsey Mason, Housing Injustice and the Summary Eviction Process: Beyond Lindsey v. Normet, 74 OK L. Rev., 2022 forthcoming; William E. Morris Inst. for Justice, Injustice in No Time: the Experience of Tenants in Maricopa County Justice Courts, June 2005, https://morrisinstituteforjustice.org/helpful-information/landlord-and-tenant/4-final-eviction-report/file; Lawyers’ Comm. for Better Housing, No time for Justice: A Study of Chicago’s Eviction Court, Dec. 2003, https://www.lcbh.org/sites/default/files/resources/2003-lcbh-chicago-eviction-court-study.pdf; Monitoring Subcomm. of the City Wide Task Force on Housing Court, 5 Minute Justice, or, “Aint nothing going on but the rent!”, 1986; Leys, supra note 1, at 6 (“[P]lenty of people who have good factual or legal defenses lose their cases by default because of the blisteringly fast nature of eviction cases and the shoddy procedural guardrails baked into the process.”).

1

McCabe & Rosen, supra note 2, at 10.

1

See, e.g., Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr., supra note 2; Dunn & Grabchuk, supra note 1, at 334–37; Kaveh Waddell, How Tenant Screening Reports Make it Hard for People to Bounce Back from Tough Times, Consumer Reports, Mar. 11, 2021, https://www.consumerreports.org/algorithmic-bias/tenant-screening-reports-make-it-hard-to-bounce-back-from-tough-times-a2331058426/; Letter from Sens. Elizabeth Warren et al. to Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Acting Dir. Dave Uejio, March 1, 2021, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/20510708-20210301-letter-to-cfpb-on-oversight-of-tenant-screening-technology-companies; Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, Bulletin 2021–03, Consumer Reporting of Rental Information, 86 Fed. Reg. 35595, 35597–98, 2021 [hereinafter “CFPB Rental Information Bulletin”].

1

See, e.g., Annemarie Cuccia, DC’s New Tenant Rights Bill Protects Voucher Holders, Seals Certain Eviction Records, The DC Line, Mar. 16, 2022, https://thedcline.org/2022/03/16/dcs-new-tenant-rights-bill-protects-voucher-holders-seals-certain-eviction-records/ (discussing how new tenant protections in DC would help renters with subsidies access housing by removing past rental history from consideration).

1

See, e.g., Breaking the Record, supra note 1, at 16–17; Leys, supra note 1; D.C. Council Comm. on Housing & Neighborhood Revitalization, Comm. Rep. on B24–0096 at 13–17, Dec. 1, 2021, https://lims.dccouncil.us/downloads/LIMS/46603/Committee_Report/B24-0096-Committee_Report1.pdf; Indiana University McKinney School of Law Health and Human Rights Clinic et al., How Indiana Courts Can Prevent Evictions: Responding to a Looming Public Health and Economic Crisis 12–13, https://mckinneylaw.iu.edu/practice/clinics/_docs/Indiana_courts_prevent_evictions.pdf; Beiers, Park & Morris, supra note 2; Network for Public Health Law, Limiting Public Access to Eviction Records, https://www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Fact-Sheet-Limiting-Public-Access-to-Eviction-Records.pdf; Caramello & Mahlberg, supra note 1; Nikki Trautman Baszynski, Eviction Records Should Be Expunged, The Appeal, May 20, 2021, https://theappeal.org/the-point/eviction-records-should-be-expunged/; McCabe & Rosen, supra note 2, at 31–32; Sabbeth, supra note 3; Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr., supra note 2; Jaboa Lake & Leni Tupper, Ctr. for Am. Progress, Eviction Record Expungement Can Remove Barriers to Stable Housing, Sep. 30, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/eviction-record-expungement-can-remove-barriers-stable-housing/; Am. Bar Ass’n., supra note 3, Guideline 10.

1

See, e.g., Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 1161.2; D.C. Code § 42–3505.09; Nev. Rev. Stat. § 40.2545; 2019 Or. Laws Chap. 351; Minn. Stat. § 484.014; Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-40-110.5(1)-(2); 735 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/9-121; ME R. Electronic Court Systems 4(C); N.Y. Real Prop. Acts § 757.

1

See, e.g., Leys, supra note 1; McCabe & Rosen, supra note 2, at 31–32; Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr., supra note 2; Lake & Tupper, supra note 7; Am. Bar Ass’n. supra note 3; D.C. Council Office of Racial Equity, Racial Equity (CORE) Impact Assessment of Bill 24–0096, Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act of 2021 9–11, Nov. 30, 2021, https://www.dropbox.com/s/nejlhn7ljj8js3y/B24-0096%20Eviction%20Record%20Sealing%20Authority%20Amendment%20Act%20of%202021.pdf?dl=0.

1

Public Housing Agency FOIAs, DocumentCloud, https://www.documentcloud.org/app?q=%2Bproject%3Atenant-screening-story-fo-49059. See also Lauren Kirchner & Matthew Goldstein, Access Denied: Faulty Automated Background Checks Freeze Out Renters, The Markup & N.Y. Times, May 28, 2020, https://themarkup.org/locked-out/2020/05/28/access-denied-faulty-automated-background-checks-freeze-out-renters; Lauren Kirchner, How We Investigated the Tenant Screening Industry, The Markup, May 28, 2020, https://themarkup.org/show-your-work/2020/05/28/how-we-investigated-the-tenant-screening-industry.

1

See, e.g., TransUnion SmartMove, https://www.mysmartmove.com/ (Advertising screening reports that let landlords “see the full picture of [their] tenant,” and listing credit reports, criminal reports, eviction reports, and “income insights report[s],” as the components included in their tenant screening reports); SafeRent Solutions, Resident Screening, https://saferentsolutions.com/resident-screening/ (listing credit reports, eviction & address history, criminal records, credit, and ID verification); Saferent Solutions, SafeRent Score, https://saferentsolutions.com/saferent-score/ (listing rent-to-income ratio, credit reports, and eviction history as the “key factors” influencing the score in a sample image of a tenant screening report).

1

In 2015 — five years before we got involved — the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless organized a coalition of “community members, service providers, advocates and District agency representatives” to address the biggest barriers to housing in DC. Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, DC Council Reduces Barriers to Rental Housing, Mar. 9, 2022, https://www.legalclinic.org/dc-council-reduces-barriers-to-rental-housing/. The group, after conducting focus groups with tenants, identified these barriers as “criminal history, rental or eviction history, credit history, voucher discrimination[,] and high fees.” Id. Before we joined in early 2020, the coalition had already convinced the DC Council to pass limits on criminal record screening for housing, D.C. Code § 42–3541, and had begun working on legislation — which has since passed — to put guardrails around the tenant screening process to combat discrimination, and to seal eviction records that do not result in a judgment in favor of the landlord, Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act of 2022, D.C. Law 24–115, https://code.dccouncil.us/us/dc/council/laws/24-115.

1

Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act of 2022, D.C. Law 24–115, https://code.dccouncil.us/us/dc/council/laws/24-115.

1

See, e.g., Eva Rosen, Testimony before the D.C. Council Committee on Housing & Neighborhood Revitalization and Committee on Government Operations, Joint Public Hearing on B23–0338, Eviction Record Sealing Authority Amendment Act of 2019, Oct. 30, 2020, https://lims.dccouncil.us/downloads/LIMS/42817/Hearing_Record/B23-0338-Hearing_Record1.pdf.

1

Natasha Duarte & Tinuola Dada, Upturn, Testimony before the D.C. Council Committee on Housing & Executive Administration, Hearing on B24–96, Eviction Record Sealing Authority Amendment Act of 2021, May 20, 2021, https://www.upturn.org/work/dc-council-testimony-on-the-eviction-record-sealing-authority-amendment-act/.

1

In recent years, several resources on drafting fair chance housing laws have been published, see, e.g., Nat’l Housing Law Project, Fair Chance Ordinances, an Advocate’s Toolkit, https://www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/021320_NHLP_FairChance_Final.pdf, and many advocates have called for eviction record sealing, see supra note 7, but we found little practical guidance on how to draft and implement eviction record sealing legislation.

1

All states allow “unconditional quit notices” in at least some instances, which bar the tenant from resolving the lease violation or unpaid rent. See Janet Portman & Ann O’Connell, State Laws on Unconditional Quit Terminations, Nolo, Jan. 26, 2022, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-laws-unconditional-quit-terminations.html.

1

Some jurisdictions, such as West Virginia, do not require notice to quit, meaning landlords can file an eviction lawsuit immediately after a lease violation without notifying the tenant. Additionally, in some jurisdictions, like Pennsylvania, landlords can waive the notice requirement in the lease agreement. For a more comprehensive list of state notice requirements, see Janet Portman & Ann O’Connell, State Laws on Termination for Violation of Lease, Nolo, Jan. 26, 2022, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-laws-termination-violation-lease.html; Ann O’Connell, State Laws on Termination for Nonpayment of Rent, Nolo, Jan. 26, 2022, https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/state-laws-on-termination-for-nonpayment-of-rent.html.

1

In some jurisdictions, like DC and New Jersey, there are two types of settlement agreements. In one, called a “consent judgment,” the landlord secures a judgment for possession, and the court will move to remove the tenant if they violate the terms of the agreement. In the other, no judgment for possession is entered and the landlord must secure this judgment before the removal process will begin. See, e.g., McCabe & Rosen, supra note 2, at 9; NJ Courts, Settlement Agreement (Tenant Remains), https://www.njcourts.gov/forms/10514_appndx_xi_v.pdf.

1

In many jurisdictions, a tenant can be removed as soon as 24 hours after the landlord obtains the writ of restitution. Tenants are also notified in advance of their scheduled removal date. See, e.g., Texas State Law Library, The Eviction Process, Jun. 1 2022, https://guides.sll.texas.gov/landlord-tenant-law/eviction-process. The writ of restitution can remain valid for several weeks. For example, in DC, a writ of restitution remains valid for 75 days. U.S. Marshals, Writs of Restitution (Evictions), https://www.usmarshals.gov/foia/Forms/pub22(7).pdf.

1

See Caramello and Mahlberg, supra note 1, at 1 n.5.

1

See Id.

1

Charging extra fees or higher fees to tenants with housing subsidies is unlawful in jurisdictions that prohibit source-of-income discrimination, see D.C. Code § 2–1402.21(g)(2)(A), and may violate federal fair housing law, see generally, e.g., U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Development, Office of Fair Housing & Equal Opportunity (FHEO) Guidance on Compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act in Marketing and Application Processing at Subsidized Multifamily Properties, Apr. 21, 2022 [hereinafter “HUD Marketing and Application Processing Guidance”] (noting that making it harder for renters with subsidies to access housing can result in unlawful disparate impacts). See also, Ben Winck, Renters of Color Have to Spend $294 More on Average than White Renters to Get an Apartment, Insider, Apr. 11, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/rental-market-expensive-people-of-color-housing-prices-real-estate-2022-4 (citing Manny Garcia & Edward Berchick, Zillow Research, Renters: Results from the Zillow Consumer Housing Trends Report 2021, Aug. 10, 2021, https://www.zillow.com/research/renters-consumer-housing-trends-report-2021-29863/).

1

For example, RealPage allows landlords to customize how the criminal record scoring model treats different offenses based on the “nature/type and severity” as well as the “degree and/or age of the offense.” Real Page, Resident Screening, https://www.realpage.com/apartment-marketing/resident-screening/. National Tenant Network’s DecisionPoint allows landlords to exclude certain criteria, such as medical collections. National Tenant Network, NTN DecisionPoint, https://ntnonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/NTN-DecisionPoint-12.14.2018.pdf.

1

See sources cited supra note 1.

1

See Katy McLaughlin, Robots are Taking Over (the Rental Screening Process), Wall Street Journal, Nov. 21, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/robots-are-taking-over-the-rental-screening-process-11574332200.

1

See supra note 11. See also Dunn & Grabchuk, supra note 1, at 323. An online search for affordable housing in DC in October 2020 returned 806 listings (including those with waitlists), 95% of which required criminal background and credit checks. We conducted this search on DCHousingSearch.org, DC’s affordable housing listing and search engine, using the filters for criminal and credit checks.

1

For example, AppFolio settled with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for allegedly failing to check whether court records purchased from a third party and used in tenant screening reports had been sealed. Complaint, U.S. Dep’t of Justice v. AppFolio, 1:20-cv-03563, Dec. 8, 2020, [https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/ecf_1-_us_v_appfolio_complaint.pdf](https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/ecf_1-_us_v_appfolio_complaint.pdf).

1

National Tenant Network, NTN DecisionPoint sample report, https://ntnonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/NTN-DecisionPoint-12.14.2018.pdf. The first page of NTN’s sample report includes the records and other information attributed to the tenant, and NTN’s “DecisionPoint” or “DecisionPoint Plus” score, and the end of the first page says “End of NTN DecisionPoint.” On the second page, NTN includes the following warning in a smaller font size than the rest of the information in the report:

“Important Notice to Users of Landlord/Tenant Civil Court Filings and Judgments – A record on file may not always represent a disposition adverse to the consumer. A Landlord/Tenant Civil Court Filing does not necessarily mean that the defendant was evicted from an apartment, found to owe rent or in violation of other lease provisions. Lawsuits may be filed in error or lack merit. These records very rarely contain SSN or date of birth information, which may make it impossible to be certain that the following filings involve your applicant. NTN recommends calling the plaintiff listed for more information. This information is provided pursuant to the NTN subscription agreement.”

Id.

1

See CT Fair Housing Ctr. v. CoreLogic Rental Property Solutions, LLC, 478 F. Supp. 3d 259, 275 (D. Conn. 2020); Colin Lecher, Automated Background Checks are Deciding Who’s Fit for a Home, The Verge, Feb. 1, 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/1/18205174/automation-background-check-criminal-records-corelogic.

1