Calculated Need: Algorithms and the Fight for Medicaid Home Care

A Comparison of Five States’ Eligibility Algorithm

Miriam Osman, Emily Paul, Emma Weil

ReportFor a summary of this report, read the fact sheet here.

Executive Summary

In the United States, millions of elderly people and people with disabilities rely on Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) to meet their daily needs — from help bathing and getting dressed to support preparing and eating meals — as well as to work and to participate in their communities. While this is a federal program, it is largely administered at the state level. As part of implementing its HCBS programs, each state is responsible for designing its own rules and systems to determine which of its residents are eligible for HCBS benefits and how much home care they should receive. Every state uses automated tools as part of determining HCBS eligibility.

Automated eligibility determinations for home and community-based services are not designed to meet people’s needs. Rather, they are better understood as political and budgetary tools designed to control access to state-provided home care benefits. These determinations are tied to the federally mandated HCBS eligibility standard, known as the institutional level of care.

The institutional level of care requirement is a product of the historical moment in which it was created, when pressure from the disability rights movement coincided with the federal government’s goal of reducing the costs of long-term care. Replacing institutional care with home care offered the promise of responding to political demands while reducing the government’s overall costs of long-term care. Yet the promised cost reductions could only be achieved by keeping home care costs down and limiting home care to those who were in, or would otherwise be in, an institution.

Our work on automated HCBS eligibility determinations has led us to the following key findings:

The institutional level of care requirement and the algorithms used to enforce it, referred to in this report as LOC algorithms, are political tools that draw a subjective line between who is deserving and undeserving of receiving care in their home in an attempt to reduce the costs of long-term care.

Every state uses automated eligibility determinations for home-based care, and every state’s calculation of the institutional level of care looks different. Someone who is considered eligible for home and community-based services in one state may not be in many others. This variation across states emphasizes that these tools do not provide objective measurements of need but instead serve the policy and budget goals of the states’ HCBS programs.

States’ use of automated tools and reliance on private vendors depoliticizes the question of who deserves home care, obscuring it as a technocratic question of how to measure eligibility. States rely on four mechanisms that depoliticize LOC algorithms: (1) focusing on accuracy, (2) deferring to vendor expertise, (3) de-emphasizing the role of the algorithm, and (4) concealing assessments and algorithms from the public.

There are no “good” automated tools for HCBS determinations. While automated tools such as LOC algorithms can be tweaked to broaden eligibility, these tweaks alone, though often necessary for harm reduction, will not actually provide a path to fully meeting people’s needs. The only way people’s needs will be met is through creating a system of universal care in which elderly people and people with disabilities have the power to define their own experiences and articulate their own needs.

At the same time, we believe that an examination of LOC algorithms can provide an important window into the logic of eligibility determinations and provide an additional avenue for people with disabilities and their advocates to challenge individual determinations, as well as the broader system. In short, advocates should understand challenges to LOC algorithms as part of a bigger fight for a different system of care.

This report examines states’ use of LOC algorithms to determine eligibility for home and community-based services. The details of LOC algorithms are often shielded from the public in many states. Through public records requests and documents released by state agencies, we have nevertheless obtained substantial information about five jurisdictions: Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Washington, DC. We use these details to guide our argument that LOC algorithms are subjective political tools that vary across states.

We begin the report with background on the fight for home care led by people with disabilities and how we ended up with the institutional level of care as the eligibility standard. Next, we provide a basic explainer of how states determine eligibility, drawing on our comparison of the five LOC algorithms we obtained. We then examine the mechanisms state agencies and vendors use to depoliticize the question of who gets home care. Case studies on how Medicaid agencies in Washington, DC, Missouri, and Nebraska worked with vendors to define and implement the institutional level of care provide detailed examples of this depoliticization in practice. Finally, we offer recommendations for advocates on accessing and analyzing their states’ LOC algorithms. We hope this can support advocates in mounting challenges that build power through developing counternarratives and collective demands in collaboration with people directly impacted by LOC algorithms.

Collective challenges to state LOC algorithms can reduce harm in the short term, while helping to build the power needed to fight for universal care in the long term. This report aims to shed light on LOC algorithms and the eligibility determination process for advocates and people served through HCBS programs. Fighting for the changes needed to meet the needs of all will require the combined, coordinated, and concerted efforts of grassroots forces, legal aid organizations, advocates, people with disabilities, care workers, and many others. We hope this report is a useful step in identifying what we are up against in order to fight for the change we need.

Key concepts

Medicaid: Medicaid is a joint federal and state health insurance program for low-income people who meet both income requirements and other requirements based on their circumstances or needs. Medicaid is administered by states with a mix of state and federal funding. States develop their own Medicaid plans governing who will be covered, what services the state will provide, and how providers will be reimbursed. These plans must be approved by the federal government and are subject to federal requirements and guidelines. Medicaid is distinct from Medicare and largely covers different populations, though some people are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. At the start of 2025, roughly 71.2 million people were enrolled in Medicaid and 68.5 million were enrolled in Medicare, with 11.9 million enrolled in both programs.

Home and community-based services (HCBS): Home and community-based services refers to long-term care that is provided outside of a nursing facility or other institutional setting. It includes care in facilities such as adult day care and assisted living. A major component of home and community-based services is personal care, which includes assistance with things such as bathing, dressing, preparing and eating food, and taking medications, as well as with household tasks such as cleaning and grocery shopping. Anyone who qualifies for Medicaid is entitled to receive institutional care. By contrast, states are not required to create HCBS programs under Medicaid, meaning people who qualify for Medicaid are not necessarily entitled to home and community-based services beyond limited personal care services that are part of Medicaid state plans. There are two optional mechanisms through which states provide the majority of their home and community-based services: waivers and state plan amendments.

HCBS waivers: Waivers are one of the optional mechanisms for states to provide home and community-based services under Medicaid. HCBS waivers were established in 1981 as an amendment to the Social Security Act. They allow states to offer home and community-based services to specific populations and to provide different services to different groups by waiving federal Medicaid requirements for states to make the same services available to everyone who qualifies for Medicaid and to use the same income and resource eligibility standard across all programs. To qualify for an elderly and physically disabled waiver program, for example, an individual would have to meet additional functional requirements related to their needs, rather than just meeting Medicaid income requirements, and they may only be able to receive care in certain parts of the state.

Activities of daily living (ADLs): Activities of daily living encompass people’s basic needs, typically including things such as mobility, bathing, dressing, eating, and toileting. An individual’s functional needs are often assessed for HCBS eligibility based on the level of assistance they require to complete different activities of daily living. States may use different terminology to describe activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living (see below), with some state regulations describing certain tasks as the former where others will describe them as the latter.

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs): Instrumental activities of daily living refer to tasks that may require more complex thinking or organization and are critical to independent living, typically including tasks such as housekeeping, managing medications, managing money, cooking, shopping, transportation, and communication. The amount of assistance an individual requires to complete certain instrumental activities of daily living is sometimes included as part of an eligibility determination.

Institutional level of care (LOC): In order to be eligible for home and community-based services, individuals must be determined to require a level of care, or LOC, that would otherwise only be met in an institutional setting, such as a nursing facility or an intermediate care facility. There is a federal requirement for all states to carry out a face-to-face, standardized eligibility assessment for HCBS waivers to determine whether individuals meet the state’s institutional level of care requirement. Yet there is no standard definition for institutional level of care enforced across the country. Rather, it is up to each state to define the institutional level of care and to determine which activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, and other factors (such as cognition, behavior, and medical needs) to include in the eligibility criteria.

Assessment: Any tool, such as a questionnaire or form, used by state agencies to gather information from people seeking home and community-based services to make eligibility determinations for HCBS waiver programs. These tools can take the shape of long questionnaires such as the interRAI Home Care (HC) assessment, one of the most commonly used assessment tools, or shorter forms designed by the state. Assessment tools are often created by vendors (private entities like interRAI, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, Pearson, and others) and adapted to a state’s requirements, used off the shelf, or vendors may develop a custom assessment in concert with the state agency. Federal requirements mandate that the assessment be conducted face-to-face and be standardized.

LOC algorithm: An automated set of instructions, written by a state agency, typically with private consultants, that uses data collected from the assessment tool as input to make a determination about whether a person meets that state’s definition of the institutional level of care. LOC algorithms vary in terms of which assessment questions they consider and how they score the questions. LOC algorithms vary across states and have minimal regulations and testing. They do not measure a person’s need but instead measure whether a person meets the state agency’s definition of who is deserving of care under the federally mandated standard.

Automated tools: Any standardized tools or logic, including but not limited to LOC algorithms. This includes decision trees, spreadsheets, code, tables, instructions, algorithms, or guides used to make or inform decisions about access to care.

Institutional bias: Under federal law, the LOC standard used for HCBS eligibility must be the same as the LOC standard for nursing facility admission. The Supreme Court also has ruled that it is a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act to unnecessarily institutionalize people who could receive care at home. In practice, however, it is much easier to qualify for nursing facility eligibility under Medicaid than it is to qualify for home and community-based services. And, once someone is found eligible, they are entitled to enter a nursing facility and have any services they need paid for by Medicaid. In contrast, even someone who has been found eligible for home and community-based services could be placed on a waitlist for years or could be given an insufficient budget to meet their needs at home. A study comparing nursing facility and HCBS assessment criteria found that the use of stricter criteria, more stringent methods of determining need, and longer assessment forms for home and community-based services in some states, as well as the longer timeframe and administrative burden these processes require, can limit access to HCBS programs, compared to access to nursing facilities. There is also less pressure to limit enrollment in nursing facilities for a variety of reasons, including systemic ableism (informing the fact that many people too readily accept that some people with disabilities “cannot” live in their own homes or communities, or would be too burdensome outside of an institution) and the fact that people’s desire to live at home instead of entering a nursing facility acts as a built-in limit on nursing facility enrollment. Finally, many people are pressured into entering nursing facilities, either because they are unable to receive the services they need through an HCBS program, because they are under guardianship and were not given a say, or because they were not informed of the array of services available to them. Together, these factors that favor placing people in institutions rather than providing access to care in homes and communities create what is termed institutional bias.

Cost containment: When the federal government expanded home and community-based services, it was under the rationale of “containing the rising costs of long term care.” State waiver programs are required to demonstrate cost neutrality, i.e., show that the waiver will cost the same as, or less than, the amount that would be spent on institutional care for the same population. Waiver programs are meant to cut costs by relying on so-called informal support (unpaid care provided by friends and family), reducing wages and benefits for care workers, and limiting access to the programs to only those who meet an institutional level of care requirement. At the same time, the government encourages privatization throughout Medicaid as an additional way of containing costs. Privatization is championed as a more efficient, cheaper option than publicly administered programs. But in reality, privatization is a way to get public funds into private pockets, while reducing avenues for accountability and transparency and cutting labor costs. The term “cost containment” is a euphemism for slashing budgets, underpaying workers, and scaling back public programs. It is strategic jargon that bureaucrats and industry experts use to make it seem like the government is doing something more sophisticated (and beneficial to the public) than it is.

I. Introduction

Disability benefits programs in the United States, including Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services, provide essential — though too often inadequate — support for people with disabilities. These programs often treat people with disabilities as untrustworthy and undeserving, as evidenced by restrictive and burdensome eligibility processes, severely limited benefits, and an emphasis on identifying individual fraud. These and other benefits programs are designed around the assumption that people are going to try “to take advantage” of the system — a racist and ableist idea that has deep social and historical roots in the United States. Benefits programs are also a product of class struggle. They were concessions won by workers and organizers for the benefit of all of society, and their systematic dismantling is an attempt to break the power of the working class and oppressed.

In July 2025, Congress passed sweeping Medicaid cuts that will strip away essential health care benefits from millions of people to fund the Trump administration’s tax cuts for the rich. While we still don’t know exactly how these cuts will affect home and community-based services, history has shown that they are a likely target. This significant attack on Medicaid coverage is part of a decades-long process — outlined, but by no means begun, in Project 2025 — to keep poor and working people barely at the threshold of survival, while the ruling class pockets the wealth of society. Welfare cuts are just one part of the story.

Further limiting who is eligible for benefits programs is one of the many ways these programs have been scaled back over time. State and private actors have built an extensive infrastructure of tools and technology to determine access to disability benefits. This infrastructure obscures the political decision to deny the right of people with disabilities to participate in society and replaces it with technocratic questions about measuring who should get benefits and how much they should get.

This report focuses on one example of this infrastructure: eligibility determinations for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services for elderly people and people with physical disabilities. HCBS programs are the primary provider of paid home care for elderly people and people with physical disabilities in the United States. Access to Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services enables people to live in their communities instead of in a nursing facility or other institution.

Starting in the 1980s, states began expanding access to home care, driven by changes in federal policy. The disability rights movement was crucial to creating the necessary pressure on legislators to invest in home care for elderly people and people with disabilities. At the same time, federal policymakers were concerned about the growing costs of long-term care in institutions. Home care offered the promise of lowering those costs for the government, while also responding to grassroots pressure for these changes.

These two pressure points informed the eligibility logic for home and community-based services. Instead of universal home care, where everyone has a right to the care they need, the US system of publicly funded home care only treats people as “deserving” of paid care at home if their state determines that they require the amount of care that is provided in a nursing facility or other institution. The goal of limiting these services only to people who would otherwise be in an institution informed Congress’s statutory requirement for states to use an institutional level of care, or LOC, metric to determine eligibility.

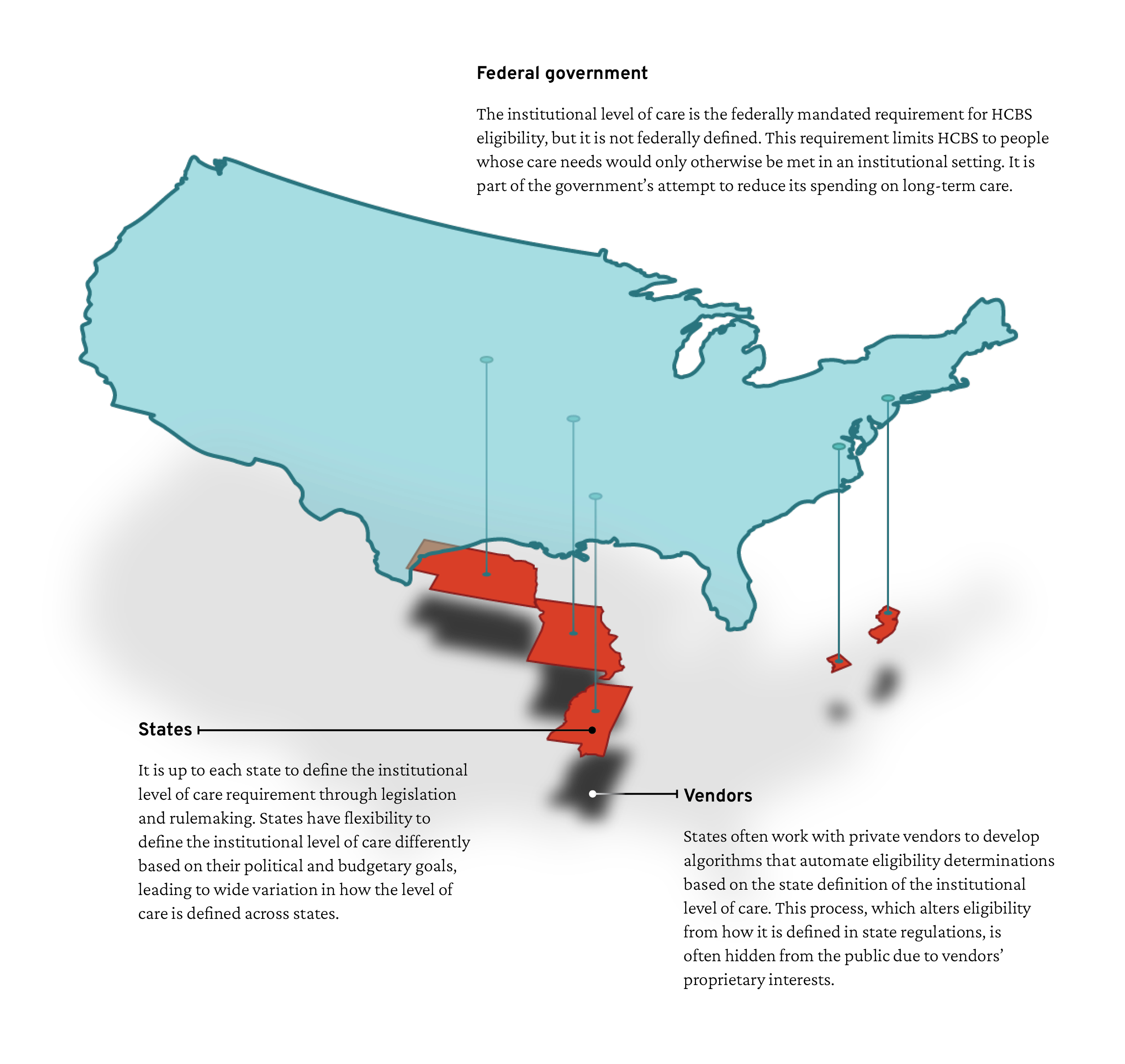

Though it is federally mandated, the institutional level of care is not defined at the federal level. Every state defines its own level of care requirement through legislation, rulemaking, and the development of a LOC algorithm, typically built by private vendors. Our own and other research show wide variation in how level of care is defined and operationalized across states. This means, for example, that someone living in New Jersey might be eligible for home and community-based services in that state, but if they were to move to Washington, DC, they might not be. This system severely limits people’s ability to live where they want to live and still get the care they need.

State Medicaid agencies frame institutional LOC algorithms as tools that ensure the “right” people get approved for home care, based on a standardized measure. In this process, measuring whether someone meets the state’s definition of the level of care is equated with whether that person needs home care. In reality, however, level of care is a misnomer. LOC algorithms do not measure how much care people need but instead enforce the state’s definition of who deserves to receive care in their home. Using standardized assessments and LOC algorithms does not make deciding who should get home care objective or fair. It merely obscures what is actually a subjective and political exercise behind claims of technical expertise and the opacity of proprietary interests. In the process, the use of standardization and automated tools depoliticizes the question of who deserves care and hinders advocacy.

The goal of this report is to shift attention from the question of whether a LOC algorithm is good toward an understanding that there is no such thing as a good LOC algorithm. LOC algorithms may be more or less harmful, but they are never “good.” Ultimately, our vision is a system of universal home care in which the institutional level of care as a barrier to care is obsolete. In the meantime, we seek to reduce the harms of LOC algorithms while also building power to demand broader access to — and more comprehensive funding for — home care for everyone who needs it.

In what follows, we begin with an overview of the origins of the institutional level of care requirement in home and community-based services and how to think about eliminating it in the future. We then explain the technical aspects of LOC algorithms to provide an understanding of how states determine who is deserving of home and community-based services. With this deeper understanding of LOC algorithms in mind, we explore the ways in which states depoliticize HCBS eligibility. Using case studies of LOC implementations in Washington, DC, Missouri, and Nebraska, we illuminate the mechanisms that state agencies and vendors use to turn the political question of eligibility determinations into a technical one. Finally, we conclude this report with a number of advocacy tools that are intended to support advocates in accessing, analyzing, and challenging LOC algorithms.

Using standardized assessments and LOC algorithms does not make deciding who should get home care objective or fair. It merely obscures what is actually a subjective and political exercise behind claims of technical expertise and the opacity of proprietary interests.

II. Dismantling the institutional level of care

The federal government’s decision to use the institutional level of care as the eligibility standard for home and community-based services was a political choice to restrict access to benefits programs. The institutional level of care is an artifact of the historical moment in which it was created. It does not measure a person’s need but rather is a way to control who is eligible for care.

The disability rights movement was crucial to creating the necessary pressure on legislators to turn away from institutional settings and towards HCBS. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, disability rights activists in the United States, inspired by the civil rights movement, organized and fought for equal rights and against discrimination, and struggled against the medical model of disability that informed the mainstream 20th century view of people with disabilities that relegated them to institutions. Within the broader work of disability rights activists from the 1960s to the 1980s, the deinstitutionalization movement exposed the appalling conditions under which many people with disabilities lived in institutions and fought to shutter the worst of these institutions. During roughly the same period, activists in the independent living movement created the first independent living centers, providing a disabled-led, community-based alternative to institutional care that supported greater autonomy and social integration for people with disabilities.

During this same period, Congress and the courts responded to dismal conditions and abuse in nursing facilities by increasing standards, regulation, and oversight. Congress also took initial steps to provide federal funding to states for home and community-based services. In the late 1970s, driven by concerns about the growing costs of long-term care, the federal government began planning a demonstration project to “test the cost-effectiveness of home and community-based services as a substitute for nursing home use.” In 1981, as part of the Reagan administration’s Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, Congress amended the Social Security Act to create HCBS waivers, initiating a program with funding incentives for states to expand access to home and community-based services.

The Reagan administration and the disability rights movement championed this expansion of home and community-based services for very different reasons. For people with disabilities and disability rights activists, expanding home and community-based services was a step forward in the provision of dignified and comprehensive care. These services would go on to improve the lives of millions of people with disabilities and elderly people, supporting them to participate in their communities.

For the Reagan administration, however, the promise of expanding home and community-based services was its potential to contain the rising costs of Medicaid long-term care expenditures. The federal government at the time was willing to allow people to access care in their own homes and communities so long as this option could further the government’s priority of reducing costs. The restrictive eligibility requirements, waitlists, and limited services that people trying to access home and community-based services face today are not inevitable, but rather reflect political choices and priorities made at a specific historical moment.

Ultimately, there was a tension between the government’s budget-slashing aims and the demand for home and community-based services from elderly people and people with disabilities (and their families) who needed care and wanted to receive it in their homes or communities rather than institutions with infamously abysmal conditions. Policymakers used the offensive term “woodwork effect” to refer to their fear that people who were not already in or about to enter institutions would “come out of the woodwork,” wanting government-funded long-term care once it was offered in the home. Similar to invocations of the “welfare queen,” the use of this term emphasized the racist and ableist class warfare that uses ideas of deservingness to make sure that nobody gets more than they “should.” Policymakers’ fear of the “woodwork effect” speaks to the belief, that persists today, that people receiving public benefits and people with disabilities are inherently untrustworthy and that HCBS programs need additional barriers to make sure that only those who are the most “deserving” of care are able to receive it.

Over forty years later, the logic of access to home and community-based services set out during the Reagan era persists. Using a restrictive definition of who deserves to receive care in their own home or community is just one of the tactics the federal government uses to keep Medicaid’s long-term care costs down. Other tactics the government uses include limiting eligibility, underpaying care workers, relying on unpaid care from family and friends, and reducing service hours. The effect is that care is denied to many people who need it. In this report, we focus on just one of these tactics: the creation of restrictive eligibility standards.

The requirement for an individual seeking home and community-based services to meet an institutional LOC standard is the main way states identify those eligible for benefits, while excluding anyone else from access to these services. While the introduction of HCBS waivers led to the expansion of Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services in states, this expansion was curtailed by the policy goal of replacing institutional care with home care, rather than making home care available to everyone who needs it.

In a universal health care system that provides long-term care to everyone who needs it, there would be no need for a binary eligibility determination, and thus no need for defining an institutional level of care. People could go through a care planning process, in which an assessment could be used to help identify the services they need and from which they would benefit, rather than using the assessment as input to a binary eligibility determination. Recognizing that resources are not infinite, this planning could even involve a prioritization process involving the person receiving the services, where individuals could choose what services they would like to prioritize for themselves.

This already happens to an extent today, through Medicaid’s benefit for children under 21, the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment. Unlike HCBS waivers, the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment program provides an array of mandatory home care services to children who need them and does not have restrictive access requirements. Arbitrarily cutting people with disabilities off from these services at age 21 and pushing them into waiver programs, rather than just providing a continuity of care, is a demonstration of the political choices made to restrict the provision of public benefits to the greatest possible extent.

It is important to note that without a political commitment to universal long-term care, eliminating the institutional level of care requirement will not solve the problem of restrictive access to home and community-based services. Rather, other tactics would simply replace the institutional level of care requirement, such as waitlists and limiting services through the care allocation and care planning processes.

Advocates already have a starting point for bigger fights for universal care through work they are doing to reduce the harms of LOC algorithms. Advocates should continue this harm-reduction work from the perspective that the institutional level of care is a political and budgetary tool rather than a legitimate measure of people’s needs. This orientation helps redirect energy from technocratic fights around making LOC algorithms fairer and toward engaging with eligibility determinations in the same way that states and vendors do — as a tool to accomplish policy goals.

In the next section, we dive deeper into how states determine eligibility for home and community-based services to give advocates a better understanding of the idea of the institutional level of care requirement as a political tool.

Advocates should continue this harm-reduction work from the perspective that the institutional level of care is a political and budgetary tool rather than a legitimate measure of people’s needs. This orientation helps redirect energy from technocratic fights around making LOC algorithms fairer and toward engaging with eligibility determinations in the same way that states and vendors do — as a tool to accomplish policy goals.

III. How states determine HCBS eligibility

Although the institutional level of care is a federally mandated standard, each state establishes its own definition of institutional level of care through state agency rulemaking. Through rulemaking, state agencies may define specific criteria and scoring, or they may simply set forth more general requirements, such as someone needing support on two or more activities of daily living. This process is subject to requirements for public notice and comment though it remains inaccessible for many people.

State agencies then contract with vendors to develop an automated eligibility determination process that implements the state’s level of care requirement. There are several types of vendors involved in the implementation of LOC algorithms:

Standardized assessment vendors, such as interRAI

Implementation vendors that build the scoring algorithms for those assessments, such as Optumas and FEI Systems

Consulting vendors that make recommendations about best practices (beyond technology) regarding waiver program design and LOC criteria in regulations, such as Mathematica, Mercer, and, again, Optumas

These vendors offer state agencies a rationale and the automated tools to determine who is eligible for home and community-based services. In doing so, these vendors often claim proprietary interests in the states’ assessment and scoring algorithms that hide these tools from public scrutiny.

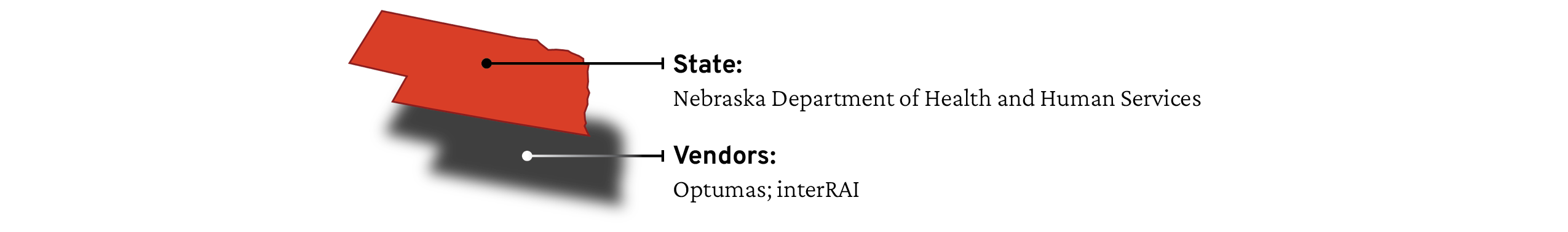

Who defines the institutional level of care requirement for HCBS eligibility determinations?

Who defines the institutional level of care requirement for HCBS eligibility determinations? This graphic illustrates how the institutional level of care is defined from the federal government down to states and their vendors. It shows the five states analyzed in our report, Nebraska, Missouri, Mississippi, Washington, DC, and New Jersey. The shadows below each state emphasize the opacity of most vendor-built tools.

Every state uses automated tools to determine eligibility for HCBS programs. Automated eligibility determinations can be broken down into two key steps:

A face-to-face standardized assessment to gather data: This is the step that is more visible to people applying for the program, their families and support people, and to legal advocates.

A LOC algorithm that calculates whether someone meets the state’s institutional LOC criteria: The algorithm is created by translating the LOC criteria in the state’s regulations into a set of instructions. This translation process often alters the criteria. Many people are not even aware that these algorithms exist and falsely perceive the standardized assessment as the determining factor for eligibility rather than the algorithm.

The eligibility determination process is largely hidden from public view, limiting opportunities for proactive advocacy or public engagement. Most people do not have insight into how automated determinations work for a variety of reasons, including vendors’ proprietary claims. States’ reliance on the private sector to create LOC algorithms further decreases transparency because these private entities are incredibly resistant to public scrutiny, are not publicly accountable, and deny the public access to basic information about their tools. Some of the most widely used assessments are developed by nonprofit research organizations, yet they still aggressively protect their proprietary interests.

Whether for- or non-profit, vendors tightly control information regarding how eligibility is determined. Even when the assessment or algorithm is created by the state Medicaid agency, it can still be difficult to access information about eligibility determinations. Our own public records requests from multiple states were denied on the basis of trade secrets exemptions and other barriers. Even when people access an algorithm, it can be difficult to understand what the algorithm actually does.

This section provides a baseline understanding of how institutional level of care is defined and operationalized. It draws on our analysis of documents obtained through public records requests and of HCBS waiver applications to explain how LOC algorithms are designed and used. In our research, we found a wide variation in how the level of care requirement is defined across states. This variation highlights that rather than being an objective measure of need, the level of care requirement and the automated systems used to measure it are political tools for states to control access to home and community-based services in line with their budget constraints and policy priorities.

The standardized assessment: Input for the algorithm

For people seeking services, the standardized assessment is the first step of the eligibility determination process. The assessments differ state by state, but they typically operationalize a medical understanding of disability that focuses on specific health and functional limitations, which allows few opportunities for individuals to contextualize or provide nuance regarding the support they require. For individuals, the assessment process can be burdensome, invasive, incredibly dehumanizing, biased in ways that make some disabilities less legible, and inaccurate in capturing a person’s actual care needs. How people answer a question on the assessment, what the assessor observes or believes the answer should be, or whether the person being assessed has a support person present can make or break whether someone receives the services they need.

Beyond the unavoidable limitations of standardization, there are myriad reasons why people’s assessments may not adequately represent their needs. People may not think about their capabilities on an average or bad day; may not remember things (such as when their last fall was); may overestimate their abilities; or may be too embarrassed to answer honestly. People also may not have a full understanding of what the possible responses to each question are and how they are used to determine eligibility. Assessors may also miss important information about a person’s needs due to oversight or bias, such as bias against particular forms of disability or based on race, gender, sexuality, or language. Overall, the assessment process can yield inadequate and inaccurate data as input for the LOC algorithm.

The interRAI HC assessment

The most widely used assessment for HCBS programs for elderly people and people with physical disabilities is the Home Care (HC) assessment created by interRAI, a vendor of assessments and algorithms that has been involved in automated HCBS determinations since the 1990s. As of 2024, the interRAI HC assessment is used in more than 25 different states. Over 100 million interRAI nursing home assessments have been completed in the US since 1990. Some states modify the interRAI HC assessment or other out-of-the-box assessments, and some design their own custom assessments. In this report, we focus on the interRAI HC assessment because it is widely used, including by the five states in our LOC algorithm comparison. Much of this analysis can be extended to other assessments and the interRAI HC is not unique in the issues it poses.

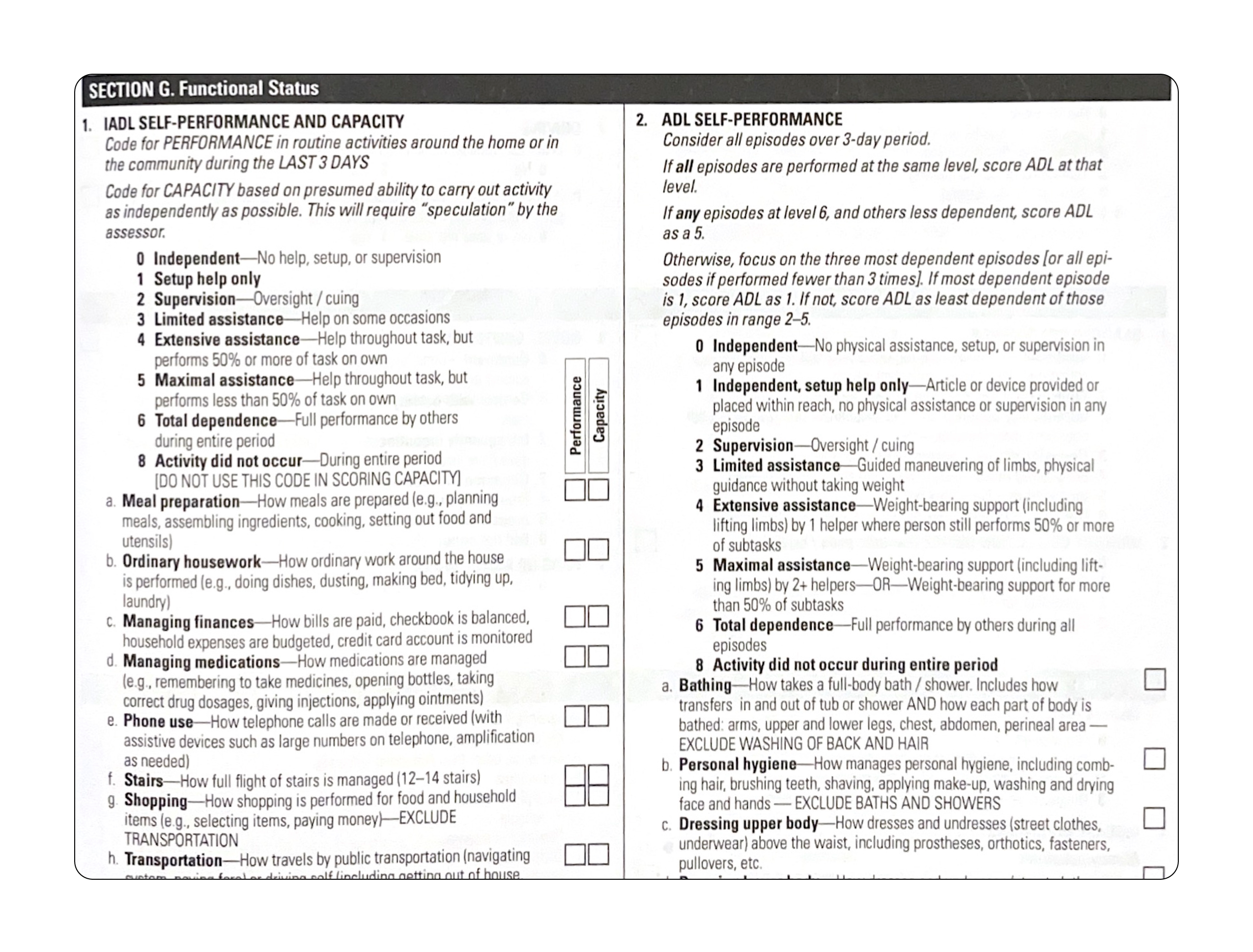

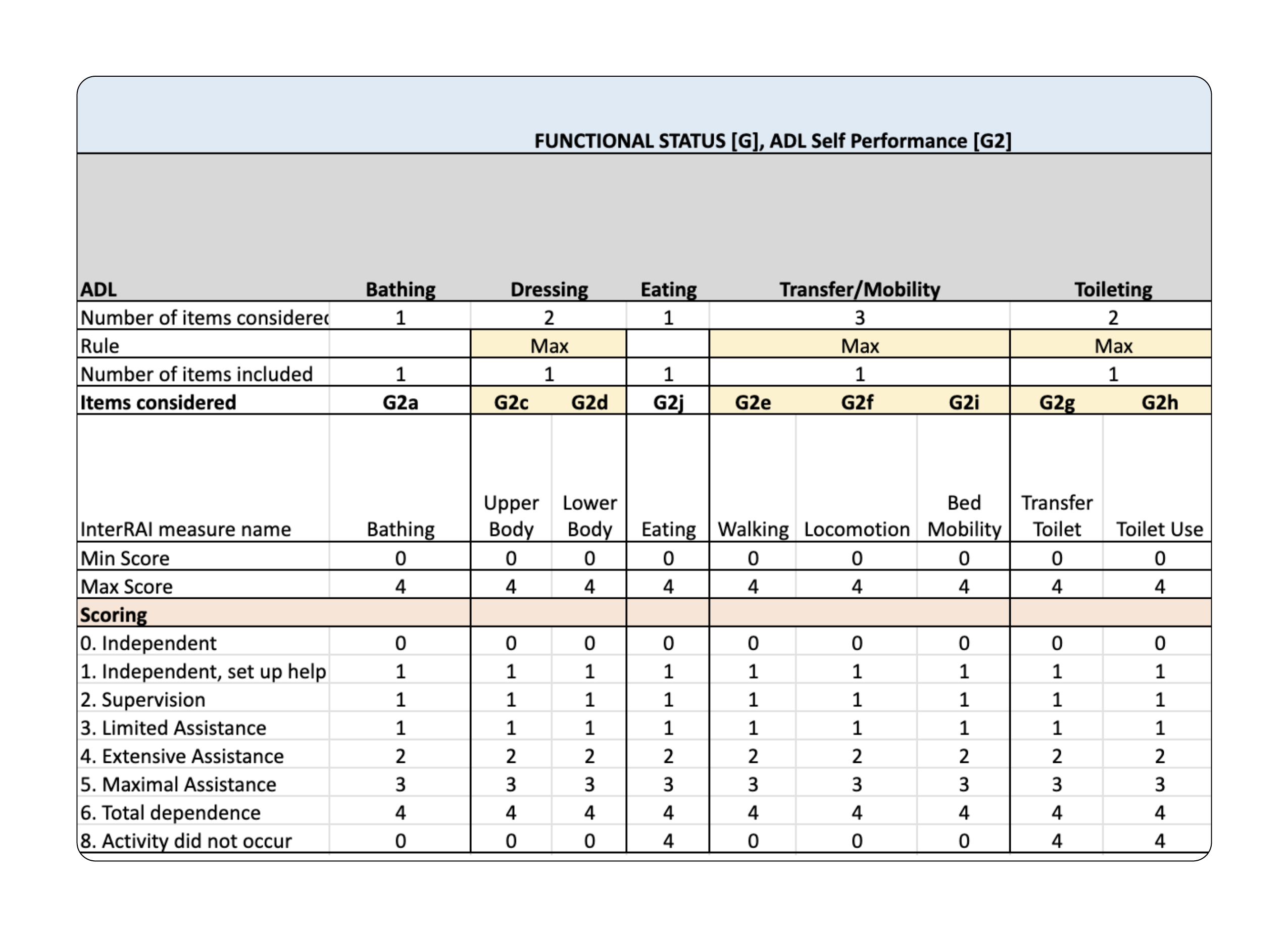

Figure 1. Functional Status Section of the interRAI HC Assessment

Figure 1. Functional Status Section of the interRAI HC Assessment. This figure, an example page taken from the widely used interRAI HC assessment, shows questions on instrumental activities of daily living and activities of daily living with scales for response options. Note the full list of activities of daily living is not pictured here because they continue on the following page of the assessment. Source: interRAI HC assessment form and user manual, standard English edition, version 9.1.

The interRAI HC contains more than 250 questions organized into 20 sections, including Functional Status, Continence, Treatments and Procedures, Health Conditions, Disease Diagnoses, Cognition, Communication and Vision, Mood and Behavior, as well as basic data gathering sections, such as Identification Information and Intake and Initial History.

States tend to rely the most on the Functional Status section in determining whether someone meets the institutional level of care requirement. The Functional Status section considers the support that people need with things such as eating, bathing, using the bathroom, and dressing (called activities of daily living, or ADLs) and with things such as grocery shopping, meal preparation, and medication management (called instrumental activities of daily living, or IADLs).

Figure 1 presents an example of the first page of the Functional Status section on the interRAI HC assessment form, and demonstrates how assessors translate an answer from someone seeking services into a numbered rating on an assessment and the potential response types on the interRAI HC assessment form. Some questions, such as the activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living shown in Figure 1, use ratings from 0–6 to quantify how much support the person needs for each activity: 0 if the person is able to do the activity completely independently to 6 if they are completely dependent on others to do the activity. If the person has not done one of the activities listed in the three days prior to the assessment, the person is rated an 8 (activity did not occur). In this report, we use the term “rating” to refer to the numerical values assigned to questions on the interRAI HC and the term “score” for how LOC algorithms use those values to determine eligibility.

Other questions on the interRAI HC have different rating options, such as those on the frequency of balance issues—from 0 (not present) to 4 (exhibited daily in the past 3 days—or bladder continence—from 0 (complete control) to 5 (no control present). Some questions, such as whether someone has pressure ulcers or other skin conditions, are rated as a binary, either 0 (not present) or 1 (present).

Many of the questions have what is called a “lookback period,” or a period of time prior to the assessment for which the assessor is supposed to consider the person’s needs. For activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, for example, the assessor is instructed to score the person based on the highest amount of support that person needed in the past three days. Some questions have a longer lookback period, such as the question about falls, which considers whether the person has had a fall in the past 90 days.

According to interRAI, each of its assessment instruments, including the Home Care assessment, “represents the results of rigorous research and testing to establish the reliability and validity of items . . .” Reliability refers to a test’s ability to consistently produce the same results, whereas validity refers to how well the test measures what it is supposed to measure. There are multiple types of both reliability and validity.

One of the main measures used to demonstrate the reliability of the interRAI HC is inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability is a measure of how similarly two different assessors score the same person on the same assessment. In practice, this metric is only able to tell us how consistently an assessment can be applied. Imagine an assessor comes to someone’s home and assesses them using the interRAI HC with its three-day lookback period for activities of daily living. This person may have fluctuating pain and mobility issues that did not flare up in the three days prior to the assessment, and as such, they might be assessed as not needing any support on activities of daily living. Yet if the assessment occurred on a different day, they would be assessed as needing support. This person could be assessed by two different people using the interRAI HC with the same results, resulting in high inter-rater reliability, while actually not fully capturing their needs.

Studies of the interRAI HC’s concurrent validity have measured alignment with established criteria. In this case, rather than comparing two different assessors using the same assessment, researchers looked at how similarly people were scored on the interRAI compared to previously established scales designed to measure needs for support and cognitive function and found what is considered “excellent agreement.”

To understand this measure of validity, imagine a scenario similar to the one outlined for reliability: An assessor comes to someone’s home and scores them on the interRAI, and a different assessor then assesses them using the other scales. The validity in this study is based on finding a strong correlation between the interRAI questions and those of the other scales. Even if neither measures the person’s needs well, this correlation could still be strong.

While there are numerous critiques of the reliability and validity of the interRAI HC and other assessments, we are primarily concerned with how state agencies and vendors act as if the reliability and validity of the assessment automatically transfers to their LOC algorithms. In reality, the algorithms are designed through a separate process and only factors in a subset of the assessment questions. By extending claims of reliability and validity from the assessments to the algorithms, state agencies and vendors fail to acknowledge the discretion involved in designing the algorithms. Most evaluations of the algorithms seem to be limited to analyzing their impacts on eligibility rates, which says nothing about the reliability or validity of the algorithm.

In reality, the algorithm is designed through a separate process and only factors in a subset of the assessment questions. By extending claims of reliability and validity from the assessments to the algorithms, state agencies and vendors fail to acknowledge the discretion involved in designing the algorithms.

LOC algorithms: Scoring the assessment to make an eligibility determination

The assessment on its own does not provide a determination about whether someone is eligible for home and community-based services under their state’s program. The way states use the assessment as input to determine HCBS eligibility varies significantly. When designing their LOC algorithms, state agencies and vendors may choose different subsets of assessment questions to include in eligibility determinations and assign different weights or scores to those questions and responses. As a result, even when states use the same assessment, their LOC algorithms can arrive at completely different conclusions. Simply knowing which assessment a state uses does not provide sufficient information to know how the institutional level of care requirement is operationalized. Despite the algorithm being crucial to understanding how the eligibility determination is made, states and vendors obscure their use of LOC algorithms and make them difficult to obtain.

Table 1.1. Comparison of Eligibility for Example HCBS Participant in Missouri

| Nebraska | New Jersey | Mississippi | Missouri | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible | Ineligible | Eligible | Ineligible | Ineligible |

| Pathway 1 | Didn’t reach activities of daily living requirement for any pathways | 87.5 points (LOC = 50) | 9 points (LOC = 18) | 7 points (LOC = 9) |

Table 1.1. Comparison of Eligibility for Example HCBS Participant in Missouri. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

To illustrate how different the scoring process can be across states, we examine and compare the use of the interRAI HC assessment in LOC algorithms in five states: Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Washington, DC. To understand how different choices state agencies and vendors make when designing an LOC algorithm can result in different eligibility determinations in different states, let’s look at an example scenario.

This example uses anonymized assessment data from someone who was receiving home and community-based services in Missouri and was then found ineligible when Missouri changed its LOC algorithm. According to their interRAI HC assessment, this person needs limited assistance with personal hygiene and dressing their lower body and needs set-up help for bathing, dressing their upper body, walking, and going to the bathroom. They need significant help with housework and shopping. They are incontinent, have consistent balance issues, and have severe pain and fatigue. They have been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, diabetes, anxiety, and depression, and have had a stroke. This person had been receiving services in Missouri for years and expressed a desire to continue to receive services so that they could stay in their home.

Based on the same exact responses on the interRAI HC assessment, this person would be eligible for home and community-based services in Nebraska and Mississippi but ineligible in New Jersey, Missouri, and DC, as shown in Table 1.1.

This variation in eligibility has to do with choices that state agencies made in regulations and the choices the agencies and their vendors made in designing their LOC algorithms. Understanding these design choices and their impact on eligibility helps identify issues with these algorithms and potential ways to reduce their harms. The key design choices are:

Scoring approach: How an algorithm calculates eligibility. Based on our research, we have identified two distinct scoring approaches in LOC algorithms: The first is a “pathways” approach, in which a person is eligible if they fulfill the requirements for one of a set of predefined categories. The second is an “accumulation” approach, in which a person is eligible if they score enough points to meet or surpass the LOC threshold.

Questions considered: Which assessment questions are included in the algorithm at all. All LOC algorithms look at only a subset of the interRAI HC questions. In some cases LOC algorithms consider different questions based on what someone is rated on another question.

Scoring the questions: How ratings on interRAI HC questions translate into points or pathways in the algorithm. Both pathways and accumulation algorithms have minimum ratings below which a question is not considered. Accumulation algorithms add different amounts of points to the overall score based on question ratings. LOC algorithms can also give more or less weight to different interRAI HC questions. This means the algorithm can be designed so that questions that the state agency and vendor consider to be more important have more of an impact on whether someone is eligible.

We’ll now discuss each in turn.

LOC algorithms use different scoring approaches

A pathways approach only considers predetermined, mutually exclusive profiles of needs—that is, each pathway corresponds with a certain “picture” of need. Pathways can include, for example: people who need assistance in a certain number of activities of daily living; people who need supervision with activities of daily living and also have certain cognitive risk factors; people who need supervision with activities of daily living and have already been in an institutional setting; and people who need some help with activities of daily living and are elderly.

Table 1.2 compares the pathways and number of questions used to measure them in New Jersey and Nebraska’s LOC algorithms (the two states of the five we studied that use the pathways approach). Each numbered description in the list is a profile of someone who meets the eligibility criteria.

Table 1.2. Comparison of Pathways Algorithms

| State | New Jersey (three pathways) | Nebraska (four pathways) |

|---|---|---|

| Pathways | 1. The individual needs at least limited assistance in at least three areas of eligible activities of daily living. 2. The individual has cognitive deficits with daily decision-making and short-term memory, and needs supervision or greater assistance in three areas of eligible activities of daily living. 3. The individual has cognitive deficits with daily decision-making and making self understood, and needs supervision or greater assistance in three areas of eligible activities of daily living. | 1. A limitation in at least three activities of daily living and one or more medical conditions or treatments. 2. A limitation in at least three activities of daily living and one or more risk factors. 3. A limitation in at least three activities of daily living and one or more areas of cognitive limitation. 4. A limitation in at least one activity of daily living and at least one risk factor and at least one area of cognitive limitation. |

| Number of interRAI HC questions used | 11 (plus one custom) | 72 |

Table 1.2. Comparison of Pathways Algorithms. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

Unlike the pathways approach, an accumulation approach is based on a person scoring enough points to meet or exceed the LOC threshold. Table 1.3 compares the number of questions, total possible points, and eligibility thresholds for the three states’ accumulation scoring algorithms in our comparison.

Table 1.3. Comparison of Accumulation Algorithms

| State | Mississippi | Missouri | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of interRAI HC questions used | 48 (plus 23 custom) | 57 | 31 |

| Total possible points | 408.5 | 129 | 31 |

| LOC Threshold | 50 points | 18 points | 9 points |

Table 1.3. Comparison of Accumulation Algorithms. Note: In Mississippi, a score between 45 and 49 prompts an additional review to see if someone should still qualify. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

Neither of the two approaches described here is necessarily more inclusive. The questions a particular algorithm considers and how it scores the questions significantly impact its determination of whether someone meets a defined LOC pathway or points threshold.

LOC algorithms consider different assessment questions

Each state in our algorithm analysis uses a different subset of questions from the interRAI HC assessment to determine eligibility. While all five states include the majority of questions about activities of daily living from the Functional Status section, their algorithms are very different. Even in states that include the same activities of daily living in their algorithms, these questions are scored differently and there is significant variation in which, and how many, other interRAI HC questions are included.

Table 1.4. Questions Considered in LOC Algorithms

| State | Mississippi | Missouri | Nebraska | New Jersey | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of interRAI HC questions used | 48 (plus 23 custom) | 57 | 72 | 11 (plus one custom) | 31 |

| Total number of sections used (out of 20 total) | 10 (plus one custom) | 11 | 13 | 3 | 5 |

| Number of activities of daily living (out of 10 total) | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 (plus one custom) | 9 |

| Number of instrumental activities of daily living (out of 8 total) | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

Table 1.4. Questions Considered in LOC Algorithms. This table compares data included in LOC algorithms by total number of questions and sections used and number of activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living used. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

The number of questions included in the LOC algorithms in our comparison ranges from 12 in New Jersey to 71 in Nebraska. Table 1.4 includes a summary of the total number of interRAI HC questions and sections and the number of activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living included in the five algorithms in our comparison.

Table 1.5. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) included in LOC Algorithms

| State | Mississippi | Missouri | Nebraska | New Jersey | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing | • | • | • | • | • |

| Personal Hygiene | • | • | • | ||

| Dressing Upper Body | • | • | • | • | • |

| Dressing Lower Body | • | • | • | • | • |

| Walking | • | • | |||

| Locomotion | • | • | • | • | • |

| Transfer Toilet | • | • | • | • | • |

| Toilet Use | • | • | • | • | • |

| Bed Mobility | • | • | • | ||

| Eating | • | • | • | • | • |

Table 1.5. Activities of Daily Living Included in LOC Algorithms. Note: New Jersey’s algorithm includes one additional custom activity of daily living called Transfer. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

None of the states in our comparison include all 10 interRAI activities of daily living. Three states do not consider Personal Hygiene, two states do not consider Bed Mobility, and three do not consider Walking. All five states, as shown in Table 1.5, include Bathing, Dressing, Locomotion, Transfer Toilet, Toilet Use, and Eating.

There is even less consistency in states’ use of instrumental activities of daily living in their algorithms, as shown in Table 1.6. New Jersey does not include any instrumental activities of daily living, and the only one included by all four of the other states is Managing Medications.

Table 1.6. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) Included in LOC Algorithms

| State | Mississippi | Missouri | Nebraska | New Jersey | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meal Prep | • | • | |||

| Housework | |||||

| Managing Finances | • | ||||

| Managing Medications | • | • | • | • | |

| Phone Use | • | ||||

| Stairs | |||||

| Shopping | • | ||||

| Transportation | • | • |

Table 1.6. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Included in LOC Algorithms. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

Beyond the activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living in the Functional Status section, states vary significantly in which other questions their algorithms consider. Washington, DC, for example, does not include any questions from the Cognition section, while Mississippi considers seven questions from that section, Missouri considers five, Nebraska considers eight, and New Jersey considers two. Table 1.7 details a full list of interRAI assessment sections and which states include at least one question from each.

Table 1.7. Sections Included in LOC Algorithms

| State | Mississippi | Missouri | Nebraska | New Jersey | Washington, DC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification Information | • | ||||

| Intake and Initial History | • | ||||

| Cognition | • | • | • | • | |

| Communication and Vision | • | • | • | • | • |

| Mood and Behavior | • | • | • | • | |

| Psychosocial Well-Being | • | ||||

| Functional Status | • | • | • | • | • |

| Continence | • | • | • | ||

| Disease Diagnoses | • | • | |||

| Health Conditions | • | • | • | ||

| Oral and Nutritional Status | • | • | • | • | |

| Skin Condition | • | • | • | ||

| Medications | |||||

| Treatments and Procedures | • | • | • | • | |

| Responsibility | |||||

| Social Supports | • | ||||

| Environmental Assessment | • | ||||

| Discharge Potential and Overall Status | |||||

| Discharge | |||||

| Assessment Information |

Table 1.7. Sections Included in LOC Algorithms. Note: Mississippi’s algorithm includes additional custom questions not included in the counts above. Source: Our LOC algorithm comparison is based on algorithms we obtained through public records requests and documents released by state agencies. See Appendix A.

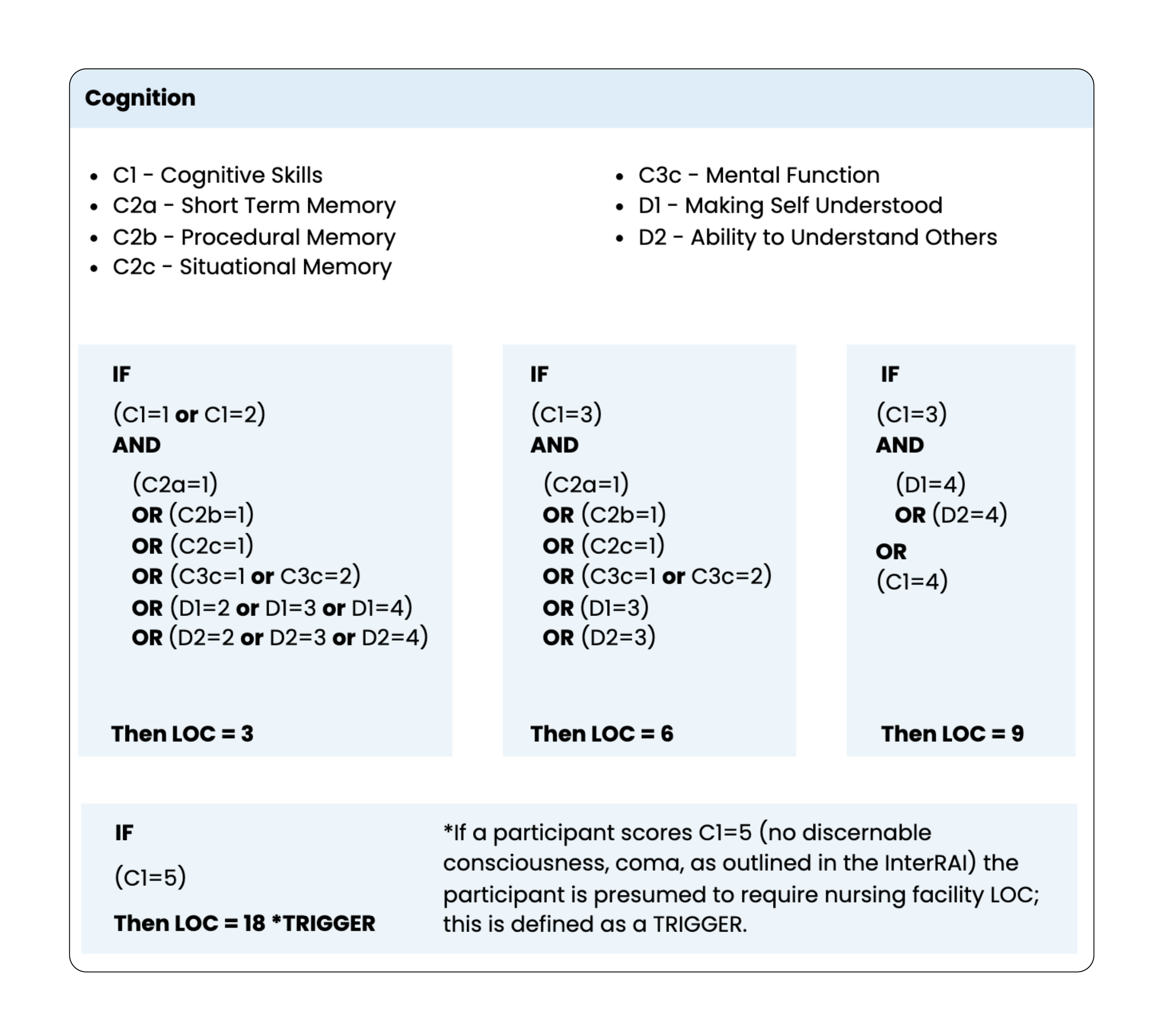

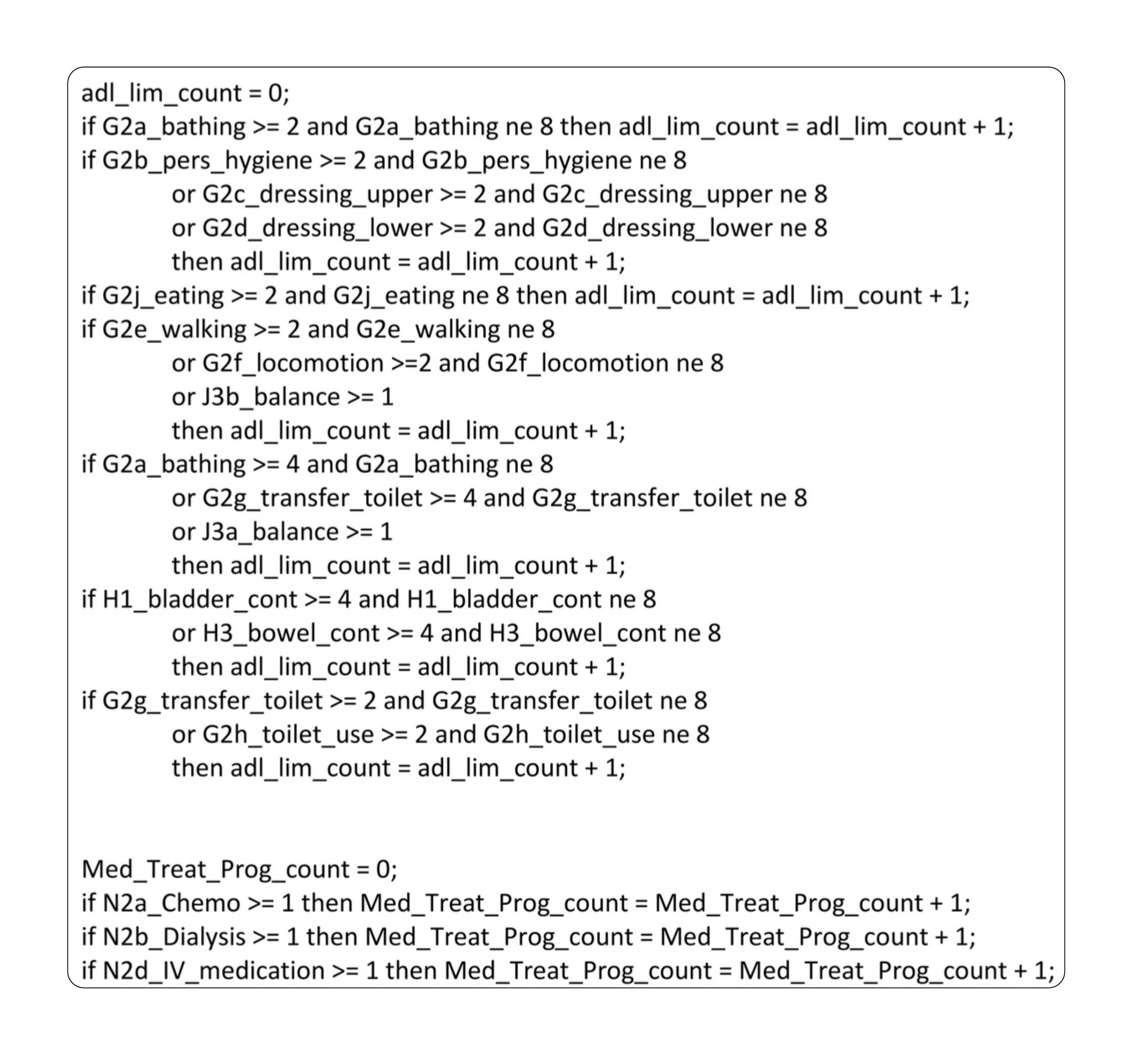

Some LOC algorithms use conditional logic so that the algorithm only considers certain questions based on someone’s rating on another question. In Missouri’s algorithm, for instance, if someone rates as having difficulty on the interRAI HC question on Making Self Understood, they only get points for that if they are also rated as having at least some level of difficulty on Cognitive Skills for Daily Decision-Making, as shown in Figure 2.

Which questions an algorithm includes is only one factor in who will be determined eligible for home and community-based services. While an algorithm that includes more questions might capture more types of need, that algorithm will not necessarily be more inclusive overall for HCBS eligibility since meeting a threshold or pathway also depends on how those questions are scored.

Figure 2. Cognition Section of Missouri’s LOC Algorithm

Figure 2. Cognition Section of Missouri’s LOC Algorithm. This figure shows the section on cognition in Missouri’s LOC algorithm, including which interRAI HC questions are included and how they are scored. Source: Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Nursing Facility Level of Care Algorithm, https://health.mo.gov/seniors/hcbs/pdf/loc-algorithm2-3.pdf.

LOC algorithms score questions using different minimum ratings and weights

In addition to deciding which questions to include and which scoring approach to use, states and their vendors have to decide how someone’s ratings on each assessment question factors into their eligibility determination. This includes setting a minimum rating on each question that determines whether to have the question factor in at all.

In Washington, DC, for example, if someone’s rating for an activity of daily living on the assessment is 1 (meaning they are able to do that activity independently after someone helps them set up) or higher (meaning they need more support), they receive points for that activity of daily living in the algorithm. Meanwhile, in Nebraska, any activities of daily living for which a person’s rating is less than 2 (meaning they need supervision to complete the activity) are not considered by the algorithm at all. And in New Jersey, activities of daily living are included if someone’s rating is a 3 (limited assistance) or higher unless they also have cognition issues, in which case their ADL needs are factored in starting at 2 (supervision). In Missouri, Eating is the only activity of daily living where a rating on the interRAI of 1 or 2 will get someone points in the algorithm, while for the other activities of daily living, a person can only get points towards the LOC score if the rating is a 3 (limited assistance) or above.

Eligibility determinations also depend on how a state’s algorithm factors specific questions into the overall score. State agencies and vendors can design the algorithm so that certain questions or sections have more weight, meaning those questions have more influence on the eligibility determination. They can also weigh different ratings on the questions differently.

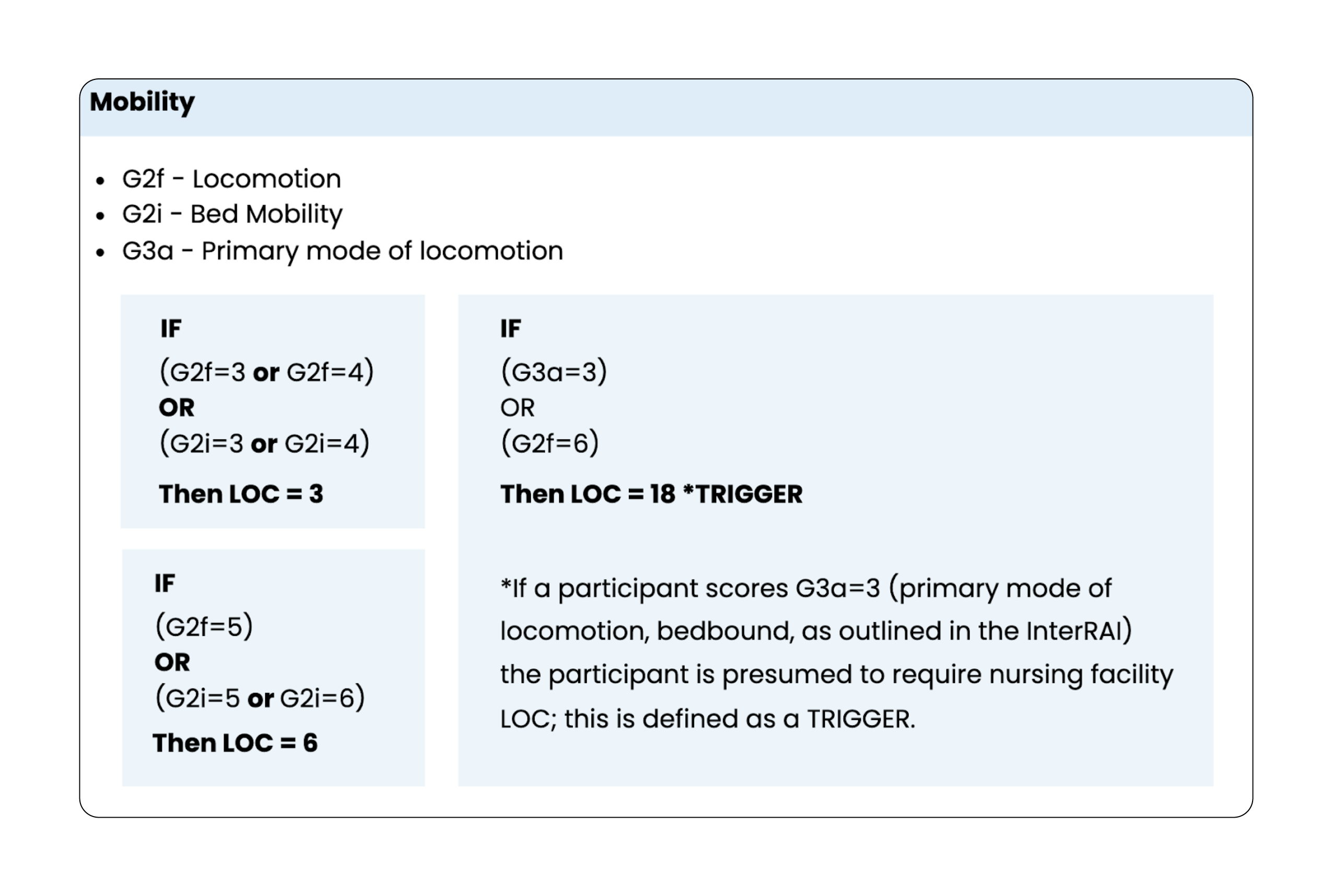

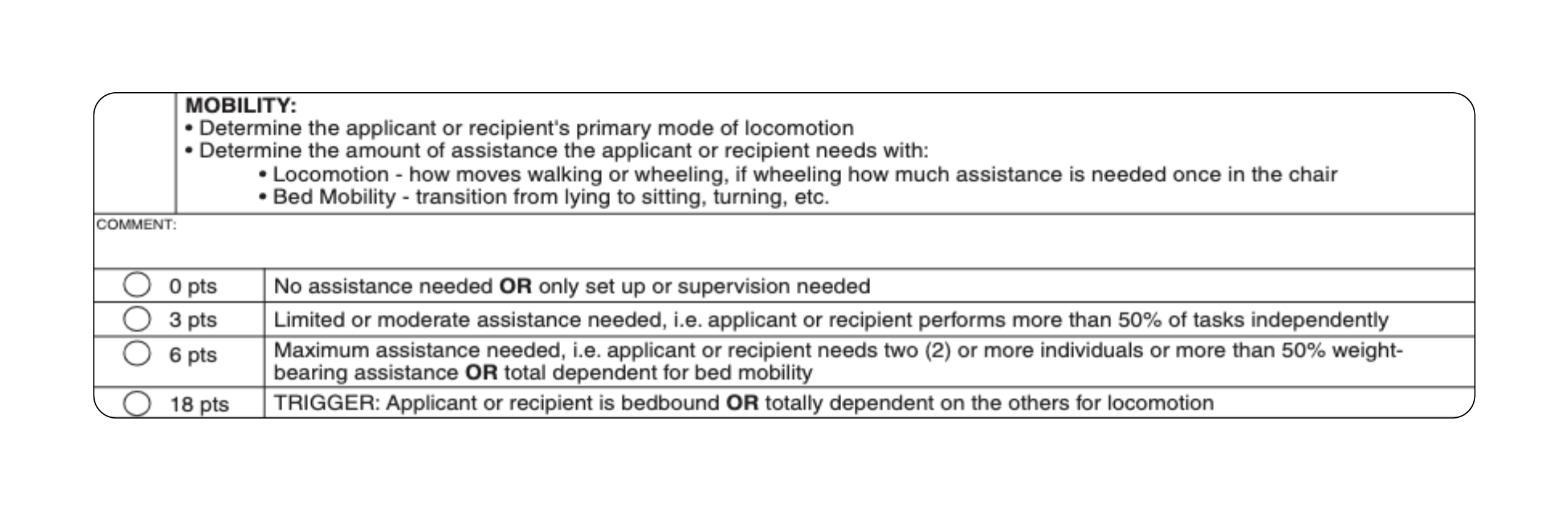

LOC algorithms can use triggers so that a rating on a single question can make someone eligible. Missouri’s algorithm has several such triggers. The trigger logic for Mobility means that if someone is bedbound or fully dependent on others to move around, they receive 18 points on that question, making them eligible, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Scoring Logic for Mobility Section of Missouri’s LOC Algorithm

Figure 3. Scoring Logic for Mobility Section of Missouri’s LOC Algorithm. This figure shows the section on mobility in Missouri’s LOC algorithm, including which interRAI HC questions are included and how they are scored. Source: Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Nursing Facility Level of Care Algorithm, https://health.mo.gov/seniors/hcbs/pdf/loc-algorithm2-3.pdf.

Algorithm design choices can reflect the priorities of each state. Any of these algorithm design choices — from the scoring approach to the weight of different questions — can be used to achieve the state’s eligibility goals. For example, someone who needs limited assistance with three activities of daily living would be eligible in New Jersey but might not qualify if they moved to DC, where, based on the ADL questions alone, their score would be 3 out of the 9 points needed to be eligible. This is because in DC’s accumulation algorithm, an interRAI HC rating of 1, 2, or 3 on an activity of daily living only gives someone one point in the algorithm, whereas New Jersey’s pathways algorithm has an eligibility pathway for people who need limited assistance or higher on three or more activities of daily living. In DC for someone to be eligible based only on three activities of daily living, they would need to have a rating of 5 (maximal assistance) on all three. (See Figure 4.1 for the scoring of activities of daily living on DC’s algorithm and Figure 4.2 for the ADL pathway in New Jersey’s algorithm.) Understanding these design choices can help advocates analyze their state’s algorithm to identify what priorities it reflects about who the state sees as deserving of home and community-based services.

Figure 4.1. Activities of Daily Living Section of DC’s LOC Algorithm

Figure 4.1 Activities of Daily Living Section of DC’s LOC Algorithm. This figure shows the activities of daily living included in DC’s LOC algorithm and how ratings on the interRAI HC translate to points in the algorithm. Source: Washington, DC, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/26054260-interrai-hc-scoring-logic-dc/.

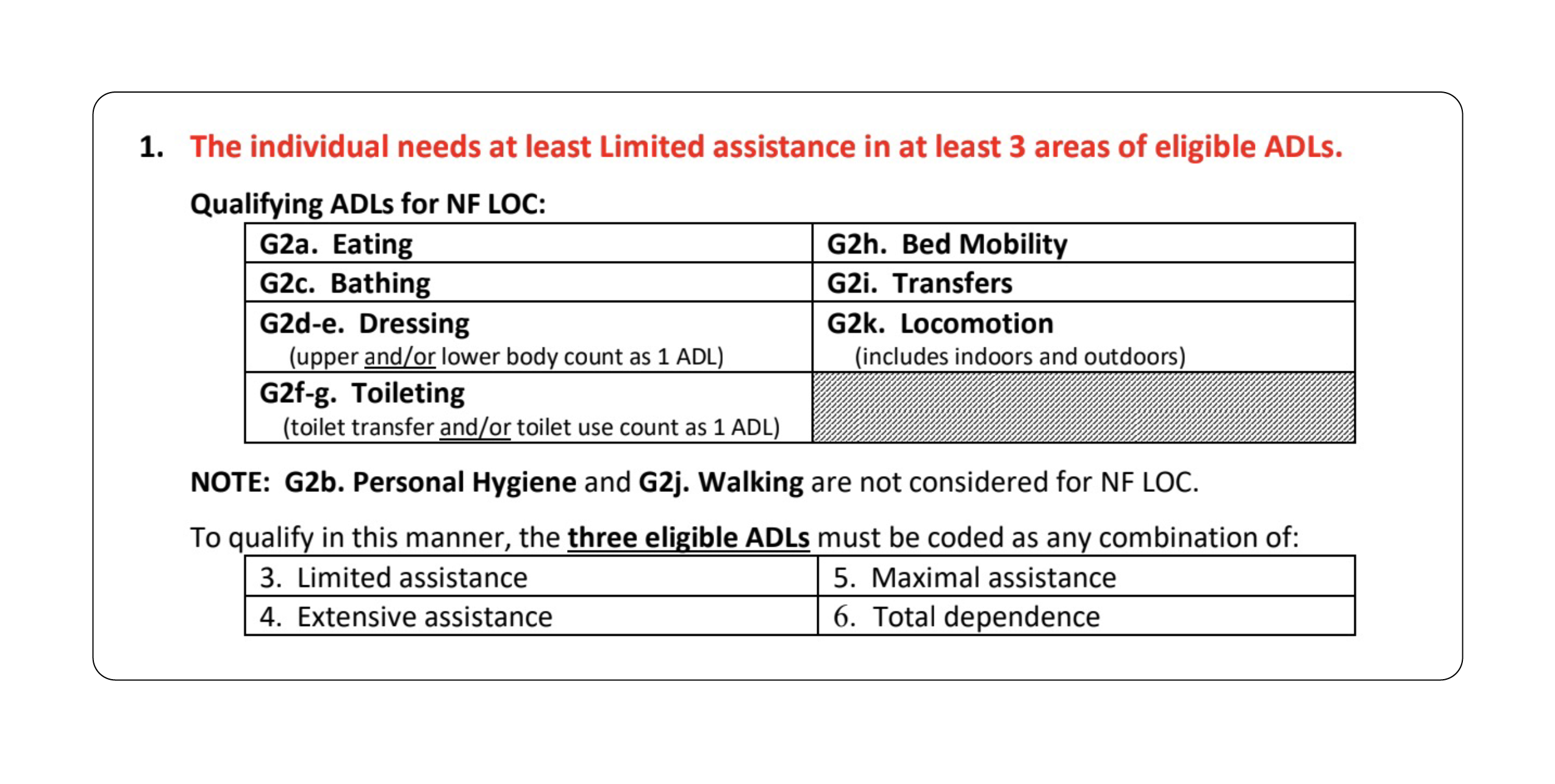

Figure 4.2. Activities of Daily Living Pathway in New Jersey’s LOC Algorithm

Figure 4.2 Activities of Daily Living Pathway in New Jersey’s LOC Algorithm. This figure shows the first pathway in New Jersey’s LOC algorithm which lists the activities of daily living and amount of assistance required to qualify. Source: See Appendix A, New Jersey, https://www.documentcloud.org/projects/222350-loc-algorithms-report-new-jersey/.

IV. How states depoliticize HCBS eligibility

The question of who is eligible to receive government-funded care is inherently political. When the federal government created HCBS waivers, it made a political choice to limit care to people who would otherwise be institutionalized. In implementing their HCBS programs, state agencies and their vendors end up reducing the political question of who deserves care to a technical question about how to define and measure institutional level of care.

States often talk about eligibility determinations as if there is an objective truth about who needs home and community-based services that can be uncovered through an objective process. The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, for example, stated that “this program will ensure the right services, to the right people, in the right setting, at the right time.” In Nebraska, one of the state’s vendors, Mercer, said that “a well-designed and comprehensive assessment instrument is intended to replace subjectivity with objectivity and inconsistency with consistency.” Other states and vendors echo similar goals.

States respond to underfunding of HCBS programs by working with vendors to create technical infrastructure to determine eligibility and then claim the eligibility determinations are fair and accurate. In doing so, states constrain the political terrain, pushing advocates toward engaging with state agencies on technical questions about assessments and algorithms.

In this report, we identify four mechanisms that are crucial for advocates to understand in order to see how state agencies obscure and depoliticize eligibility determinations:

Focusing on accuracy: State agencies claim that their automated determinations can identify the “right people” — i.e., those who “should” be eligible for HCBS programs. In reality, LOC algorithm design yields politically tolerable rates of eligibility denials, while still denying care to people who need it.

Deferring to vendors: Standardized assessments and vendors’ recommendations heavily influence state rulemaking and algorithm design. States justify their eligibility determinations by pointing to vendor decisions, invoking the validity and reliability of the vendors’ assessments. Vendor choices about how to phrase and score questions result in LOC algorithms that alter and often narrow states’ regulatory definitions of the institutional level of care.

De-emphasizing the role of LOC algorithms: In public materials, state agencies focus discussion on the selection and administration of the standardized assessment and rarely discuss the extensive and subjective process of developing the algorithm that actually determines eligibility using the assessment as input.

Concealing assessments and algorithms: State agencies rarely make the standardized assessment and accompanying materials, such as user manuals, publicly available and almost never make the algorithm available, invoking vendors’ proprietary interests to protect this information from scrutiny — even in the face of due process claims and, in some cases, court orders.

In this section, we explore these four mechanisms in practice through case studies in Washington, DC, Missouri, and Nebraska. We focus on these three jurisdictions because we were able to obtain more substantial information about their algorithm implementation process. We hope that advocates will do this exercise for their own states. We provide some tips on doing so in the Advocacy Tools section of this report and encourage advocates interested in analyzing their states’ LOC algorithms to reach out to us for support.

Case studies

The following case studies draw on documents we obtained through our public records requests, as well as documents released by state agencies, to provide a view into the design and implementation of LOC algorithms. Looking at rulemaking to refine the institutional level of care in Washington, DC, for example, reveals the interRAI HC assessment’s heavy influence on the regulations and the local Medicaid agency’s resistance to making the assessment available to people who are denied eligibility.

Meanwhile, the Missouri case study shows how mapping the state LOC regulations to the LOC algorithm narrowed who is deemed eligible for home and community-based services. This contrasts with Missouri’s nursing facility eligibility, which is more inclusive despite relying on the same regulations. In contrast to most states, Missouri published draft and final versions of its LOC algorithm on the state agency website. The state agency’s transparency about the algorithm and development process enabled us to examine the ways in which the state uses the interRAI HC and LOC algorithm to legitimize its eligibility determinations.

Lastly, our case study on Nebraska uses vendor reports and minutes from meetings between the state agency and its vendor to show how the vendor shaped eligibility in the state — highlighting, as one of the consultants is quoted as saying to state agency employees in the meeting minutes, that “the idea of LOC and eligibility being clear cut is a myth.”

Case study: Washington, DC

In July 2018, DC’s Medicaid agency, the Department of Health Care Finance, began using a new process to determine eligibility for all long-term care for elderly people and people with physical disabilities, including institutional care in a nursing facility. DC worked with its vendor FEI Systems Inc. to switch to using interRAI’s HC assessment and developed a new LOC algorithm. Of the 1,591 people whose eligibility was redetermined between July 2018 and April 2019, 14 percent lost access to home and community-based services because they did not meet the new level of care requirement.

Defining DC’s Institutional Level of Care

As part of the switch to the interRAI HC and the new LOC algorithm, the Department of Health Care Finance went through two rulemaking processes to update its eligibility regulations. The first, from November 2016 to July 2017, updated the LOC criteria and scoring. The second, from February 2019 to April 2021, “update[d] the requirements of the Long Term Care Services and Supports assessment process to align with the new standardized needs-based assessment tool [the interRAI HC] utilized by the District.”

The agency deferred significantly to the interRAI HC assessment in its rulemaking process. One example of the influence of the interRAI HC on DC’s regulations is in the definition of the lookback period, or the period of time prior to the assessment that the assessor asks about and that is used to determine people’s needs. For most questions, the interRAI HC uses a lookback period of three days. Prior to the switch to the interRAI HC, DC used a seven-day lookback period.

In their comments on the proposed rule, legal advocates from Disability Rights DC at University Legal Services and Legal Counsel for the Elderly raised concerns that the new lookback period is too short to accurately assess people’s needs. The agency’s response was that “the three (3) day look-back period for the functional assessment is the length required by the standardized assessment tool now utilized by DHCF (interRAI HC) to provide a more precise understanding of an individual’s current care and support needs while reducing the likelihood of recall errors common with longer look-back periods.” The agency went on to argue that if the three days prior to someone’s assessment do not reflect their typical needs, they could request to reschedule their assessment or request a reassessment — actions that add further delays and administrative burden to an already-burdensome process.

Despite this seeming deference to interRAI, the Department of Health Care Finance’s algorithm does not use all of the questions on the interRAI HC assessment. The agency chose not to include the interRAI HC Meal Prep question in its LOC scoring, for example, even though its previous assessment tool did ask about meal preparation needs as part of the question on eating. In the InterRAI HC assessment, Meal Prep is a separate instrumental activity of daily living, distinct from the Eating activity of daily living. The Department of Health Care Finance or its vendor therefore chose to adopt the Eating question from the interRAI assessment but not the Meal Prep question. As a result, DC’s new LOC algorithm no longer considers whether someone needs help with meal preparation, a departure from both DC’s previous assessment and from the interRAI HC assessment. In fact, the agency decided not to include any of the interRAI HC instrumental activities of daily living in the algorithm except for Medication Management.

The agency’s rulemaking process also protected and enshrined interRAI’s proprietary interests. The proposed rule suggested making a copy of the assessment and user manual available for inspection in-person at the agency’s office, which Legal Counsel for the Elderly pointed out would be difficult or impossible for people who are homebound. In their comments on the February 2019 proposed rule, both University Legal Services and Legal Counsel for the Elderly recommended that the Department of Health Care Finance instead make a copy of the assessment and the user manual available on its website. University Legal Services argued that not making the assessment available for review online, as the previous assessment had been, “fail[ed] to constitute legally sufficient notice prior to the denial, reduction, or termination of [Long Term Care Services and Supports].”

The agency’s response to these comments was to state that “the InterRAI Home Care (HC) Assessment System is a proprietary tool with copyright protections that restrict its reproduction or transmittal.” It went on to say that its licensing agreement prohibited the posting of the assessment and user manual online. Meanwhile, the interRAI HC assessment and user manual is available for purchase on interRAI’s website for $71.95.

University Legal Services also recommended that in order to meet due process requirements, the Department of Health Care Finance should provide assessment and scoring reports to anyone who receives a denial, reduction, or termination of benefits. The agency responded, “DHCF does not agree that the inclusion of completed assessment reports and scores is necessary for compliance with the notice and due process requirements described above.”

University Legal Services commented that the LOC algorithm “fails to incorporate dementia into the cognitive/behavioral score.” The agency responded that “instead of looking at whether an individual has been formally diagnosed with dementia, the cognitive/behavioral assessment evaluates the presence and frequency of a variety of behaviors and abilities, many of which correspond to the symptoms of dementia.” The LOC algorithm’s Cognitive Score includes questions from two sections of the interRAI HC: Section D, Communication and Vision, and Section E, Mood and Behavior. In addition to omitting the interRAI HC question on diagnosis of dementia, the algorithm also does not include any questions from Section C, Cognition.

The agency’s responses to advocates’ comments on the proposed eligibility rule demonstrate a deference to the interRAI HC in some areas, such as to justify using a three-day lookback period and denying online access to the assessment. While in other moments, such as to justify not including any Cognition questions from the interRAI HC, DHCF’s responses defer to its own algorithm, designed by a different vendor. The advocates’ comments and the agency’s responses demonstrate the contestable and subjective nature of what is factored into an eligibility determination.

Case study: Missouri

Missouri’s Department of Health and Senior Services is unique in our review because the agency made its LOC algorithm publicly available, both as it was going through revisions and once it was finalized. Missouri’s process of updating its LOC scoring and the algorithm that implements them began in 2017, after the state legislature made multiple changes to Medicaid long-term care with the goal of reducing spending. This included raising the LOC score required to be eligible for home and community-based services from 21 to 24 points.

Defining Missouri’s Institutional Level of Care

With the new higher LOC threshold, the Department of Health and Senior Services was concerned that people were losing eligibility who it did not think should be, so the agency decided to embark on an “LOC Transformation” project to revise the way the LOC score was determined. The stated goal for this project was “to review all aspects of the HCBS assessment process to ensure the right services are provided to the right individuals at the right time.”