What ISPs Can See

Clarifying the technical landscape of the broadband privacy debate

Aaron Rieke, David Robinson, and Harlan Yu

ReportIntroduction

In 2015, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reclassified broadband Internet service providers (ISPs) as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act. This shift triggered a statutory mandate for the FCC to protect the privacy of broadband Internet subscribers’ information. The FCC is now considering how to craft new rules to clarify the privacy obligations of broadband providers.

Last week, the Institute for Information Security & Privacy at Georgia Tech released a working paper whose senior author is Professor Peter Swire, entitled “Online Privacy and ISPs.”Throughout this report, we refer to the February 29, 2016 version of the Swire paper, which may change in the future. The paper describes itself as a “factual and descriptive foundation” for the FCC as the Commission considers how to approach broadband privacy. The paper suggests that certain technical factors limit ISPs’ visibility into their subscribers’ online activities. It also highlights the data collection practices of other (non-ISP) players in the Internet ecosystem.

We believe that the Swire paper, although technically accurate in most of its particulars, could leave readers with some mistaken impressions about what broadband ISPs can see. We offer this report as a complement to the Swire paper, and an alternative, technically expert assessment of the present and potential future monitoring capabilities available to ISPs.

We observe that:

1. Truly pervasive encryption on the Internet is still a long way off. The fraction of total Internet traffic that’s encrypted is a poor proxy for the privacy interests of a typical user. Many sites still don’t encrypt: for example, in each of three key categories that we examined (health, news, and shopping), more than 85% of the top 50 sites still fail to encrypt browsing by default. This long tail of unencrypted web traffic allows ISPs to see when their users research medical conditions, seek advice about debt, or shop for any of a wide gamut of consumer products.

2. Even with HTTPS, ISPs can still see the domains that their subscribers visit. This type of metadata can be very revealing, especially over time. And ISPs are already known to look at this data — for example, some ISPs analyze DNS query information for justified network management purposes, including identifying which of their users are accessing domain names indicative of malware infection.

3. Encrypted Internet traffic itself can be surprisingly revealing. In recent years, computer science researchers have demonstrated that network operators can learn a surprising amount about the contents of encrypted traffic without breaking or weakening encryption. By examining the features of network traffic — like the size, timing and destination of the encrypted packets — it is possible to uniquely identify certain web page visits or otherwise obtain information about what the traffic contains.

4. VPNs are poorly adopted, and can provide incomplete protection. VPNs have been commercially available for years, but they are used sparsely in the United States, for a range of reasons we describe below.

We agree that public policy needs to be built on an accurate technical foundation, and we believe that thoughtful policies, especially those related to Internet technologies, should be reasonably robust to foreseeable technical developments.

We intend for this report to assist policymakers, advocates, and the general public as they consider the technical capabilities of broadband ISPs, and the broader technical context within which this policy debate is happening. This paper does not, however, take a position on any question of public policy.

Four Key Technical Clarifications

1. Truly pervasive encryption on the Internet is still a long way off.

Today, a significant portion of Internet activity remains unencrypted. When a web site uses the unencrypted Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), an ISP can see the full Uniform Resource Locator (URL) and the content for any web page requested by the user. Although many popular, high-traffic web sites have adopted encryption by default, a "long tail" of web sites have not.

The fraction of total traffic that is encrypted on the Internet is a poor guide to the privacy interests of a typical user. The Swire paper argues that "the norm has become that deep links and content are encrypted on the Internet," basing its claim on the true observation that "an estimated 70 percent of traffic will be encrypted by the end of 2016." However, this number includes traffic from sites like Netflix, which itself accounts for about 35% of all downstream Internet traffic in North America.

Sensitivity doesn't depend on volume. For instance, watching the full Ultra HD stream of The Amazing Spider-Man could generate more than 40GB of traffic, while retrieving the WebMD page for “pancreatic cancer” generates less than 2MB. The page is 20,000 times less data by volume, but likely far more sensitive than the movie. (WebMD has yet to offer users the option of secure HTTPS connections, much less to make that option the sole or default choice.)

We conducted a brief survey of the 50 most popular web sites in the each of three categories — health, news and shopping — as ranked by Alexa.

The Long Tail of Unencrypted Web Traffic: Alexa Top 50 Sites, by Category

| Category | Percent of Sites that Do Not Encrypt Browsing by Default | Example URLs for Unencrypted Web Sites |

|---|---|---|

| Health | 86% | http://webmd.com/hiv-aids/guide…http://mayclinic.org/…cancer…http://medicinenet.org/…eczema…http://health.com/sexual-healthhttp://who.int/…childhood-hearing-loss… |

| News | 90% | http://nytimes.com/…tax-tips…http://huffingtonpost.com/divorcehttp://video.foxnews.com/…sex-after-50…http://time.com/…gay-rights…http://bankrate.com/debt-management… |

| Shopping | 86% | http://ikea.com/…bathroom…http://target.com/…study-bible…http://macys.com/…maternity-clothes…http://bedbathandbeyond.com/…acne-wash…http://toysrus.com/…Toddler-Toys… |

We found that the vast majority of these web sites — more than 85% of sites in each of the three areas — still do not fully support encrypted browsing by default. These sites included references on a full range of medical conditions, advice about debt management, and product listings for hundreds of millions of consumer products. For these unencrypted pages, ISPs can see both the full web site URLs and the specific content on each web page. Many sites are small in data volume, but high in privacy sensitivity. They can paint a revealing picture of the user’s online and offline life, even within a short period of time.

Sites struggle to adopt encryption. From the perspective of one of these unencrypted web sites, it can be very challenging to migrate to HTTPS, especially when the site relies on a wide range of third-party partners for services including advertising, analytics, tracking, or embedded videos. In order for a site to migrate to HTTPS without triggering warnings in its users’ browsers, each one of the third-party partners that site uses on its pages must support HTTPS.

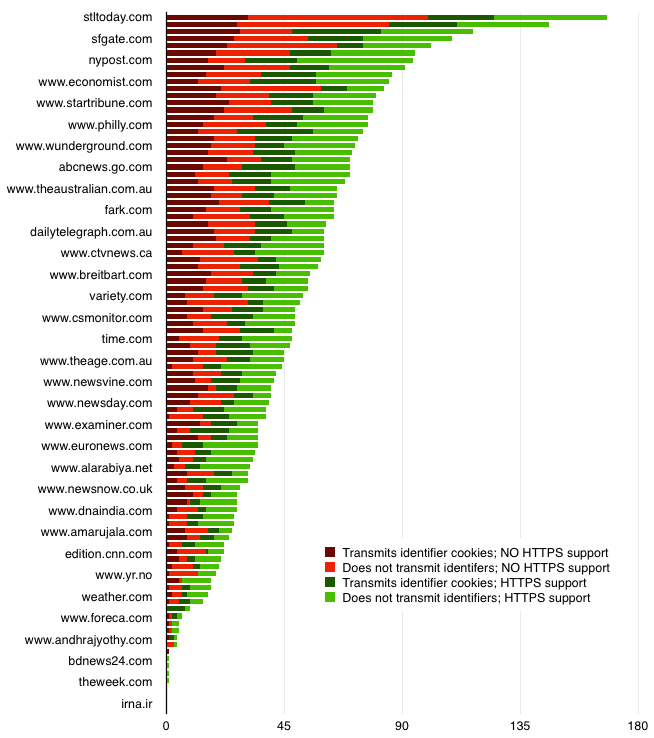

Ad tracker HTTPS support rates on the Alexa top 100 news sites (via Citizenlab)

Getting third-party partners to support HTTPS is a serious hurdle, even for sites that want to make the switch. For example, in a 2015 survey of 2,156 online advertising services, more than 85% did not support HTTPS. Moreover, as of early 2015, only 38% of the 123 services in the Digital Advertising Alliance’s own database supported HTTPS. In the figure above, describing the top 100 news sites, each unit of red or burgundy indicates a third-party partner that does not support HTTPS. In order for any one of these news sites to provide its content to users securely (without creating warning or error messages) the publisher must either wait for all of its red and burgundy partners to turn green, or else abandon those partners on any secure parts of its site. The online advertising industry is working to improve its security posture, but clearly there remains a long road ahead.

Internet of Things devices often transmit data without encryption. It’s not only web sites that fail to encrypt traffic transmitted over broadband connections. Many Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as smart thermostats, home voice integration systems, and other appliances, fail to encrypt at least some of the traffic that they send and receive. For example, researchers at the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton recently found a range of popular devices — from the Nest thermostat to the Ubi voice system, to the PixStar photo frame — transmitting unencrypted data across the network. “Investigating the traffic to and from these devices turned out to be much easier than expected,” observed Professor Nick Feamster.

As more users adopt mobile devices, they communicate with a greater number of ISPs. Use of mobile devices is growing rapidly as a portion of users’ overall Internet activity. The Swire paper observes that today’s ISPs face a more “fractured world” in which they have a “less comprehensive view of a user’s Internet activity.” It is true that today, many consumers’ personal Internet activities are spread out over several connections: a home provider, a workplace provider, and a mobile provider. However, a user often has repeated, ongoing, long-term interactions with both her mobile and her wireline provider. Over time, each ISP can see a substantial amount of that user’s Internet traffic. There’s plenty of activity to go around: The amount of time U.S. consumers spend on connected devices has increased every year since 2008.

2. Even with HTTPS, ISPs can still see the domains that their subscribers visit.

The increased use of encryption on the Web is a substantial privacy improvement for users. When a web site does use HTTPS, an ISP cannot see URLs and content in unencrypted form. However, ISPs can still almost always see the domain names that their subscribers visit.

DNS queries are almost never encrypted. ISPs can see the visited domains for each subscriber by monitoring requests to the Domain Name System (DNS). DNS is a public directory that translates a domain name (like bankofamerica.com) into a corresponding IP addresses (like 171.161.148.150). Before the user visits bankofamerica.com for the first time, the user’s computer must first learn the site’s IP address, so the computer automatically sends a background DNS query about bankofamerica.com.

Even if connections to bankofamerica.com are encrypted, DNS queries about bankofamerica.com are not. In fact, DNS queries are almost never encrypted. ISPs could simply monitor what queries its users are making over the network.

Collection and use of DNS queries by ISPs is practical, is cost effective, and happens today on ISP networks. Because the user’s computer is assigned by default to use the ISP’s DNS server, the ISP is generally capable of retaining and analyzing records of the queries, which the users themselves send to the ISP in the normal course of their browsing. The Swire paper asserts that it “appears to be impractical and cost-prohibitive” to collect and use DNS queries, but cites no technical or other authority for that assessment. Our technical experience indicates that logging is both feasible and relatively cheap to do: Modern networking equipment can easily log these requests for later analysis. Moreover, even if the user’s computer is specially configured to use an external DNS server (not operated by the user’s ISP), the DNS queries must still reach that external server unencrypted, and those queries must still travel over the ISP’s network, creating the opportunity to inspect them.

In fact, ISPs already do monitor user DNS queries for valid network management purposes, including to detect potential infections of malicious software on user devices. Certain domain names are used solely by malicious software tools, and real user traffic can be analyzed to identify and block such domains. Moreover, when an individual user visits a compromised domain, this is a strong sign that one or more of that user’s devices is infected, and commercially available tools allow ISPs to notify the user about the potential infections. According to literature from a network equipment vendor, Comcast currently deploys this security-focused, per-subscriber DNS monitoring functionality on its network.

Researchers in 2011 also found that several small ISPs were already leveraging their role as DNS providers to not only monitor, but actively interfere with, DNS resolution for their users. To be clear, we are not aware of any evidence that large ISPs have yet begun to use DNS queries in privacy-invasive ways, much less to interfere with subscribers’ queries along the lines detected in 2011. We observe here only that it is technologically feasible today for ISPs both to monitor and to interfere with DNS queries.

Although network security is not substantially impacted by a modest to moderate amount of VPN usage, there are meaningful engineering downsides to a future in which most or all DNS queries are cryptographically concealed from the end user’s ISP. (Such a future could, for example, make it more difficult for ISPs to provide early and detection and swift response for some kinds of malware attacks.) At the same time, as long as the user’s DNS queries are visible to the ISP for network management purposes, the ISP will also have a technologically feasible option to analyze those queries in ways that would compromise user privacy.

Even a short series of visited domains from one subscriber can be sensitive. A pivotal moment in a user’s life, for example, could generate the following log at the user's ISP (assuming the user hasn't invested in special privacy tools):

Over a longer period of time, metadata can paint a revealing picture about a subscriber’s habits and interests. As other policy discussions have made clear in recent years, metadata is very revealing over time. For example, in the context of telephony metadata, the President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies found that “the record of every telephone call an individual makes or receives over the course of several years can reveal an enormous amount about that individual’s private life.” The Group went on to note that “[i]n a world of ever more complex technology, it is increasingly unclear whether the distinction between ‘meta-data’ and other information carries much weight.”

This reasoning applies with equal strength to domain names, which we believe are likely to be even more revealing than telephone records. Such a list of domains could also indicate the presence of various “smart” devices in the subscriber’s home, based on the known domains that these devices automatically connect to.

3. Encrypted Internet traffic itself can be surprisingly revealing.

Encryption stops ISPs from simply reading content and URL information directly off the wire. However, it is important to understand that encryption still leaves open a wide variety of other, less direct methods for ISPs to monitor their users if they chose.

A growing body of computer science research demonstrates that a network operator can learn a surprising amount about the contents of encrypted traffic without breaking or weakening encryption. By examining the features of the traffic — like the size, timing and destination of the encrypted packets — it is possible to uniquely identify certain web page visits or otherwise reveal information about what those packets likely contain. In the technical literature, inferences reached in this way are called “side channel” information.

Some of these methods are already in use in the field today: in countries that censor the Internet, government authorities are able to identify and disrupt targeted data access based on its secondary traits even when access is encrypted. Concerningly, such nations often rely on Western technology vendors, whose advanced products allow censors increasingly to analyze and act on traffic at “line speed” (that is, in real time, as the data passes through a network).

The side channel methods that we describe below are likely not used (or at least not widely used) by ISPs today. But as encryption spreads, these techniques might become much more compelling. Policymakers should have a clear understanding of what’s possible for ISPs to learn, both now and in the future.

Identifying specific sites and pages. Web site fingerprinting is a well-known technique that allows an ISP to potentially identify the specific encrypted web page that a user is visiting. This technique leverages the fact that different web sites have different features: they send differing amounts of content, and they load different third-party resources, from different locations, in different orders. By examining these features, it’s often possible to uniquely identify the specific web page that the user is accessing, despite the use of strong encryption when the web site is in transit.

Researchers have published numerous studies on the topic of web site fingerprinting. In one early study using a relatively basic technique, researchers found that approximately 60% of the web pages they studied were uniquely identifiable based on such unconcealed features. Later studies have introduced more advanced techniques, as well as possible countermeasures. But even with various defenses in place, researchers were still able to distinguish precisely which out of a hundred different sites a user was visiting, more than 50% of the time.

This body of research illustrates that decrypting a communication isn’t necessarily the only way to “see” it. The Swire paper asserts that “[w]ith encrypted content, ISPs cannot see detailed URLs and content even if they try.” To be fully accurate, however, that claim requires qualification: ISPs generally cannot decrypt detailed URLs and content. But, this class of research demonstrates that with some amount of effort, it would indeed be feasible for ISPs to learn detailed URLs (and through those URLs, in some instances, the actual content of web pages) in a range of real-world situations.

The autocomplete feature on Google’s search engine.

Deriving search queries. Popular search engines — like Google, Yahoo and Bing —provide a user-friendly feature called auto-suggest: after the user enters each character, the search engine suggests a list of popular search queries that match the current prefix, in an attempt to guess what the user is searching for. By analyzing the distinctive size of these encrypted suggestion lists that are transmitted after each key press, researchers were able to deduce the individual characters that the user typed into the search box, which together reveal the user’s entire search query.

Inferring other “hidden” content. Researchers have applied similar methods to infer the medical condition of users of a personal health web site, and the annual family income and investment choices of users of a leading financial web site — even though both of those sites are only reachable via encrypted, HTTPS connections. (Again, the researchers obtained these results without decrypting the encrypted traffic.) Other researchers of side-channel methods have been able to reconstruct portions of encrypted VoIP conversations, and user actions from within encrypted Android apps.

Such examples have led researchers to conclude that side-channel information leaks on the web are “a realistic and serious threat to user privacy.” These types of leaks are often difficult or expensive to prevent. There has been significant computer science research into practical defenses to defeat these side-channel methods. But as one group of researchers concluded, “in the context of website identification, it is unlikely that bandwidth-efficient, general-purpose [traffic analysis] countermeasures can ever provide the type of security targeted in prior work.”

These methods are in the lab today — not yet in the field, as far as we know. But the path from computer science research to widespread deployment of a new technology can be short.

4. VPNs are poorly adapted, and can provide incomplete protection.

One way that subscribers can protect their Internet traffic in transit is to use a virtual private network (VPN). VPNs are often found in business settings, enabling employees who are away from the office to connect securely over the Internet to their company’s internal network (often with setup help from the employer’s IT department). When using a VPN, the user’s computer establishes an encrypted tunnel to the VPN server (say, the one operated by the employee’s company) and then, depending on the VPN configuration, sends some or all of the user’s Internet traffic through the encrypted tunnel.

The Swire paper presents VPNs (and other encrypted proxy services) as an up-and-coming source of protection for subscribers. However, there are reasons to question whether VPNs will in fact have a significant impact on personal Internet use in the United States.

U.S. subscribers rarely make personal use of VPNs. VPNs have been commercially available for years, but they are used sparsely in the United States. According to a 2014 survey cited by the Swire paper, only 16% of North American users have used a VPN (or a proxy service) to connect to the Internet. This figure describes the percent of users who have ever used a VPN or a proxy before — not those who use such services on a consistent or daily basis, which is what protection from persistent ISP monitoring would actually require. Moreover, many of the 16% of users who have used a VPN are likely business users, rather than personal users looking to protect their privacy. It is fair to conclude that only a very small number of U.S. users actually use a VPN or proxy service on a consistent basis for personal privacy purposes.

Moreover, several adoption hurdles are likely to deter unsophisticated users. Reliable VPNs can be costly, requiring an additional paid monthly subscription on top of the user’s Internet service. They also slow down the user’s Internet speeds, since they route traffic through an intermediate server. (There are free VPN services available, but subscribers generally get what they pay for.)

Relative to other countries, the rate of VPN use in the U.S. is among the lowest in the world. VPN use is much more pronounced in other countries like Indonesia, Thailand and China, where Internet users turn to VPNs a way to circumvent online censorship, and to actively gain access to restricted content.

VPNs are not a privacy silver bullet. The use of VPNs and encrypted proxies merely shifts user trust from one intermediary (the ISP) to another (the VPN or proxy operator). In order to more thoroughly protect their traffic from their ISP, a subscriber must entrust that same traffic to another network operator.

Furthermore, VPNs may not protect users as well as the Swire paper might lead readers to believe. The paper states that “Where VPNs are in place, the ISPs are blocked from seeing . . . the domain name the user visits.” But this is not always true: whether ISPs can see the domain names that users visit depends entirely on the user's VPN configuration — and it would be quite difficult for non-experts to tell whether their configuration is properly tunneling their DNS queries, let alone to know that this is a question that needs to be asked. This is particularly common for Windows users.

Conclusion

Today, ISPs can see a significant amount of their subscribers’ Internet activity, and have the ability to infer substantial amounts of sensitive information from it. This is especially true when that traffic is unencrypted. However, even when Internet traffic is encrypted using HTTPS, ISPs generally retain visibility into their subscribers’ DNS queries. Detailed analysis of DNS query information on a per-subscriber basis is not only technically feasible and cost-effective, but actually takes place in the field today. Moreover, ISPs and the vendors that serve them have clear opportunities to develop methods of inferring important information even from encrypted data flows. VPNs are one tool that subscribers can use to protect their online activities, but VPNs are poorly adopted, can be difficult to use, and often provide incomplete protections.

We hope that this report will contribute to a more complete understanding of the technical capabilities of broadband ISPs, and the broader technical context within which the broadband privacy debate is happening.

About This Report

This report is designed to provide technical grounding for policymakers and other interested parties, regarding the extent of ISP visibility into the activities of their subscribers.

The report aims to provide technical information only, and is not intended to take a position on any matter of public policy.

Readers who identify any factual errors in this report, or who have other feedback regarding its contents, are warmly invited to contact us at hello@teamupturn.com. This report was supported by the Media Democracy Fund.

1

Federal Communications Commission, Protecting and Promoting the Open Internet, No. 14-28, 30 FCC Rcd. 5601, 2015 WL 1120110 (FCC Feb. 26, 2015) (reclassifying broadband Internet service providers as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act).

1

See generally 47 U.S.C. § 222 (concerning the privacy of customer information in the context of telecommunications services). See also H.R. Rep. No. 104- 458, at 204 (1996) (Conf. Rep.).

1

See generally Federal Communications Commission, “Public Workshop on Broadband Consumer Privacy” (Apr. 2015), https://www.fcc.gov/news-events/events/2015/04/public-workshop-on-broadband-consumer-privacy.

1

Peter Swire et al., “Online Privacy and ISPs: ISP Access to Consumer Data is Limited and Often Less than Access by Others” (Feb. 29, 2016), http://www.iisp.gatech.edu/sites/default/files/static/reports/2016/what-isps-can-see/images/online_privacy_and_isps.pdf (hereinafter “Swire paper”). Throughout this report, we refer to the February 29, 2016 version of the Swire paper, which may change in the future.

1

Swire paper, at 6.

1

See generally Swire paper, at 6-14.

1

Swire paper, at 36-37.

1

Swire paper, at 3.

1

Sandvine, “Global Internet Phenomena Spotlight: Encrypted Internet Traffic” at 4 (2015), https://www.sandvine.com/downloads/general/global-internet-phenomena/2015/encrypted-internet-traffic.pdf (hereinafter “Sandvine 2015 report”).

1

Alexa, Top Sites by Category, http://www.alexa.com/topsites/category (last visited March 5, 2016).

1

To compile the figures in the table above, we visited each site listed in Alexa’s “Top Sites by Category” listings for the categories of Health, News, and Shopping sing the Google Chrome web browser on March 5, 2016. We counted a web site as having “Encrypted Browsing Enabled by Default” if the site used an HTTPS connection after clicking through the web site (e.g., looking up a particular medical condition, reading news stories, or browsing product listings). Many shopping web sites, including Amazon.com, switch to HTTPS only after a user initiates a checkout process or access a private account page. However, because such web sites still transmitted lots of “shopping” behavior over HTTP connections, we did not classify them as “Encrypted Browsing Enabled by Default.”

1

Eitan Koningsburg, Rajiv Pant & Elena Kvochko, “Embracing HTTPS,” N.Y. Times - OPEN blog (Nov. 13, 2015), http://open.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/11/13/embracing-https. (“To successfully move to HTTPS, all requests to page assets need to be made over a secure channel. It’s a daunting challenge, and there are a lot of moving parts. We have to consider resources that are currently being loaded from insecure domains — everything from JavaScript to advertisement assets.”) (hereinafter “Embracing HTTPS”).

1

Embracing HTTPS (“Considering the importance of advertisements, this is very likely to be a significant hurdle to many media organizations’ implementation of HTTPS.”).

1

Andrew Hilts, “Some impressions on Internet advertiser security,” The Citizen Lab (Mar. 30, 2015), https://citizenlab.org/2015/03/some-impressions-on-internet-advertiser-security.

1

Id.

1

Brendan Riordan-Butterworth, “Adopting Encryption: The Need for HTTPS,” IAB (Mar. 25, 2015), http://www.iab.com/adopting-encryption-the-need-for-https.

1

Nick Feamster, “Who Will Secure the Internet of Things?,” Freedom to Tinker (Jan. 29, 2016), https://freedom-to-tinker.com/blog/feamster/who-will-secure-the-internet-of-things.

1

Id.

1

Id.

1

Swire paper, at 24.

1

Danyl Bosomworth, “Mobile Marketing Statistics compilation,” Smart Insights (Jul. 22, 2015), http://www.smartinsights.com/mobile-marketing/mobile-marketing-analytics/mobile-marketing-statistics.

1

S. Bortzmeyer, DNS Privacy Considerations, Internet Engineering Task Force, August 2015, https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7626 (“Almost all this DNS traffic is currently sent in clear (unencrypted).”). In addition, aside from DNS, an encrypted connection sometimes exposes its own domain name by design, in the headers of the encrypted packets. This is called Server Name Indication (SNI). We won’t get into the technical weeds here about SNI, but suffice it to say that there are multiple ways for ISPs to collect this information.

1

Swire paper, at 15 (claiming that “it appears to be impractical and cost-prohibitive” for ISPs to collect and use DNS lookup data).

1

See, e.g., Xerocole Partners with Damballa for Botnet Detection on Carrier Networks, Press Release (Aug. 6, 2012), http://www.reuters.com/article/idUS129911+06-Aug-2012+BW20120806 (explaining that “Damballa CSP protects some of the largest cable and wireless ISP networks in the world. By monitoring DNS activity to detect infected subscribers, Damballa CSP is a ‘light weight,’ highly scalable and powerful solution for identifying network abuse and infected subscribers.”) (emphasis added.)

1

See, e.g., Manos Antonakakis, Roberto Perdisci, David Dagon, Wenke Lee & Nick Feamster, “Building a Dynamic Reputation System for DNS,” 19th USENIX Security Symposium, Washington D.C. (Aug. 11, 2010), available at https://www.usenix.org/legacy/event/sec10/tech/full_papers/Antonakakis.pdf (describing a security system that “uses passive DNS query data[,] builds models of known legitimate domains and malicious domains, and uses these models to compute a reputation score for a new domain indicative of whether the domain is malicious or legitimate,” noting that the authors “have evaluated [the system] in a large ISP’s network with DNS traffic from 1.4 million users,” and observing that the system “can identify malicious domains with high accuracy (true positive rate of 96.8%) and low false positive rate (0.38%), and can identify these domains weeks or even months before they appear in public blacklists.”).

1

See, e.g., Damballa CSP: Advanced Threat Protection for Communication Service Providers (product brochure), available at https://www.damballa.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Damballa-CSP.pdf (explaining that the company’s system “monitors DNS traffic [of] millions of subscribers” with “[z]ero impact to network performance,” “[a]utomatically detects compromised subscriber IP addresses,” “[c]aptures malicious queries and correlates findings to generate infection reports,” and “[e]nables subscriber notification” so that subscribers can disinfect their machines).

1

Id. (quoting an unnamed Comcast executive as saying that “Comcast is using botnet detection service from Damballa to recognize the command-and-control servers and will notify customers whose computers are found to be communicating with those servers.”).

1

Chao Zhang et al., “Inflight Modifications of Content: Who Are the Culprits?,” LEET (2011), https://www.usenix.org/legacy/event/leet11/tech/full_papers/Zhang.pdf. See also Nate Anderson, “Small ISPs use ‘malicious’ DNS servers to watch Web searches, earn cash,” Ars Technica (Aug. 5, 2011), http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/news/2011/08/small-isps-turn-to-malicious-dns-servers-to-make-extra-cash.ars.

1

See generally The President’s Review Group on Intelligence and Communications Technologies, “Liberty and Security in a Changing World” (Dec. 12, 2014), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/2013-12-12_rg_final_report.pdf (hereinafter “President’s Intelligence Review”); see also Testimony of Edward W. Felten, “Senate Hearing on Continued Oversight of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act” (Oct. 2, 2013) at 8, available at http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~felten/testimony-2013-10-02.pdf (“Although this metadata might, on first impression, seem to be little more than “information concerning the numbers dialed,” analysis of telephony metadata often reveals information that could traditionally only be obtained by examining the contents of communications. That is, metadata is often a proxy for content.”); see also Jonathan Mayer, “MetaPhone: The Sensitivity of Telephone Metadata” (Mar. 12, 2014), http://webpolicy.org/2014/03/12/metaphone-the-sensitivity-of-telephone-metadata.

1

President’s Intelligence Review, at 116-117.

1

President’s Intelligence Review, at 120-121.

1

Nick Feamster, “Who Will Secure the Internet of Things?,” Freedom to Tinker (Jan. 29, 2016), https://freedom-to-tinker.com/blog/feamster/who-will-secure-the-internet-of-things.

1

See e.g., Citizenlab, “Behind Blue Coat: Investigations of commercial filtering in Syria and Burma” (Nov. 9, 2011), https://citizenlab.org/2011/11/behind-blue-coat.

1

See e.g., Shuo Chen, Rui Wang, XiaoFeng Wang & Kehuan Zhang, “Side-Channel Leaks in Web Applications: a Reality Today, a Challenge Tomorrow,” at 3 (2010), available at http://research.microsoft.com/pubs/119060/WebAppSideChannel-final.pdf (hereinafter “Web Side Channels”).

1

See Qixiang Sun, Daniel R. Simon, Yi-Min Wang, Wilf Russell, Venkata N. Padmanabhan & Lili Qiu, “Statistical Identification of Encrypted Web Browsing Traffic” (2002), available at http://research.microsoft.com/apps/pubs/default.aspx?id=69918.

1

See Xiang Cai, Xin Cheng Zhang, Brijesh Joshi & Rob Johnson, “Touching from a Distance: Website Fingerprinting Attacks and Defenses” (2012), available at https://www3.cs.stonybrook.edu/~xcai/fp.pdf.

1

Swire paper, at 23.

1

Web Side Channels, at 6. (“Interestingly, the auto-suggestion in fact causes a catastrophic leak of user input, because the attacker can effectively disambiguate the uer’s actual input after every keystroke by matching the size of the response carrying the suggestion list.”). The Swire paper asserts that “[w]hen the search is performed over an HTTPS connection, as has become the norm, the ISP can only see which search engine was used . . . but not the search query . . . .” However, while it is true that ISPs can no longer directly observe the search query in plaintext on the wire, that is not the ISP’s only option. An ISP that mimics the technique demonstrated by these researchers might still learn the search queries that users entered.

1

See Web Side Channels.

1

See Andrew M. White, Austin R. Matthews, Kevin Z. Snow & Fabian Monrose, “Phonotactic Reconstruction of Encrypted VoIP Conversations: Hookt on fon-iks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, at 3-18 (May 2011), available at http://www.cs.unc.edu/~fabian/papers/foniks-oak11.pdf.

1

See Mauro Conti, Luigi V. Mancini, Riccardo Spolaor & Nino V. Verde, “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking: Identification of User actions on Android Apps via Traffic Analysis” (Jul. 2014), available at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1407.7844.pdf.

1

Web Side Channels, at 1.

1

Kevin P. Dyer, Scott E. Coull, Thomas Ristenpart & Thomas Shrimpton, “Peek-a-Boo, I Still See You: Why Efficient Traffic Analysis Countermeasures Fail,” at 1 (2012), available at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6234422.

1

Swire paper, at 34 (“At least 30 million people in the U.S. use a VPN or other proxy service . . . This number likely will climb sharply in coming years.”).

1

This statistic is actually larger than the fraction of users that are relevant to this discussion, since many proxy services are not encrypted. Jason Mander, “GWI Infographic: VPN Users,” GlobalWebIndex (Oct. 24, 2014), http://www.globalwebindex.net/blog/vpn-infographic.

1

William Van Winkle, “The Pros and Cons Of Using A VPN Or Proxy Service,” Tom’s Hardware (Mar. 28, 2015), http://www.tomshardware.com/reviews/vpn-vs-proxy-service,4087.html (“You do get what you pay for.”).

1

GlobalWebIndex, “The Missing Billion,” at 9 (2014), http://insight.globalwebindex.net/hs-fs/hub/304927/file-1631708567-pdf/GWI_The_Missing_Billion_2014.pdf?t=1441899050488 (“It’s abundantly clear that VPN usage is most pronounced in fast-growth nations. . . . In contrast, usage is considerably less common in the most mature internet markets – with the USA, Canada, France, the UK, Australia and Japan coming at the very bottom of the table.”); Chris Smith, “Seriously Dark Traffic: 500 Mil. People Globally Hide Their IP Addresses,” Digiday (Nov. 18, 2013), http://digiday.com/publishers/vpn-hide-ip-address-distort-analytics (“Fifty percent of these 410 million VPN users say they just want access to better entertainment content, according to a GlobalWebIndex survey of 170,000 individuals spread across 32 countries. Twenty-eight percent say they do so for access to news and social networking sites, and to remain anonymous.”).

1

Id.

1

Swire paper, at 31. (“Where VPNs are in place, the ISPs are blocked from seeing the deep links and content (as with other encryption), and also the domain name the user visits.”).

1

Vasile C. Perta, Marco V. Barbera, Gareth Tyson, Hamed Haddadi & Alessandro Mei, “A Glance through the VPN Looking Glass: IPv6 Leakage and DNS Hijacking in Commercial VPN clients”, 1 Proc. Privacy Enhancing Technologies 84 (2015), available at https://petsymposium.org/2015/papers/02_Perta.pdf (“In particular, Windows does not have the concept of global DNS settings, rather, each network interface can specify its own DNS. Due to the way Windows processes a DNS resolution, any delay in a response from the VPN tunnel may trigger another DNS query from a different interface, thus resulting in a leak. . . . Under certain configurations, some VPN clients do not change the DNS settings, leaving the host’s existing DNS server as the default. For instance, we observed that the desktop version of HideMyAss (v1.17) does not set a custom DNS when using OpenVPN.”).

Related Work

This project maps the ways that data at scale may pose risks to philanthropic priorities and beneficiaries, identifies key questions that funders and grantees should consider before undertaking data-intensive work, and offers recommendations for funders to address emergent data ethics issues.

Across the FieldHow and where, exactly, does big data become a civil rights issue? This report begins to answer that question, highlighting key instances where big data and civil rights intersect.

Across the FieldOur empirical research showed that Facebook itself can skew the delivery of job and housing ads along race and gender lines, even when advertisers target broad audiences.

Across the FieldThis report is the most comprehensive examination of U.S. law enforcement’s use of mobile device forensic tools. Our research shows that every American is at risk of having their phone forensically searched by law enforcement.

Policing